Fig. 1. View of the Swiss Plateau from the Lägern mountain ridge (Aargau) - one of Switzerland's diverse forest landscapes. Systematic long-term observations are essential for the early detection of ongoing changes. Photo: Martin Moritzi (WSL)

Swiss forests are diverse, but slow in responding to changes. Climate change, air pollution and invasive pests have been affecting forests for decades - with effects on soil condition, water availability, biodiversity and stand stability. It is therefore important to determine critical values for forest decline, because it can take many decades for forest functions to be restored. This requires systematic long-term monitoring, which has become a key pillar of forest and environmental policy since the debates on “forest dieback” in the 1980s.

From environmental problem to coordinated forest monitoring

In 1979, numerous countries adopted the Geneva Convention on Long-Range Air Pollution within the framework of the UN Economic Commission for Europe (UN-ECE). This was their response to increasing cross-border air pollution and its visible consequences (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Altenberg in the Ore Mountains, Saxony, 1991. For the pollutant sulphur dioxide, the annual mean concentrations in the air in the 1980s here were sometimes over 300–400 µg/m³, and the immissions of acidifying sulphur brought with the rain were around 200 kg/ha per year. This led to the acidification and depletion of the weakly buffered soils. The trees suffered both from chemical burns to their needles and from a lack of nutrients, and died off over large areas. Photo: L. Vesterdal.

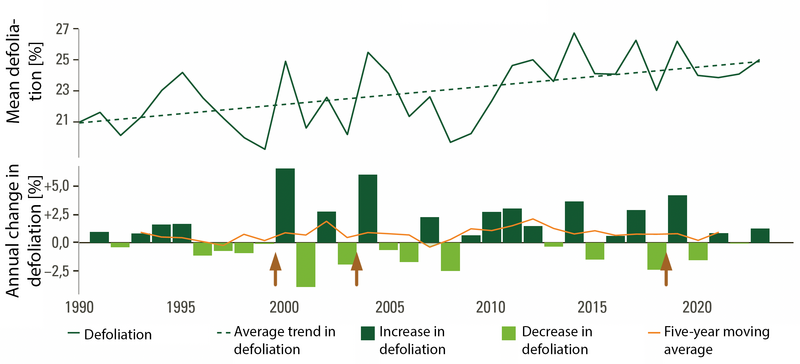

Within the framework of this convention, the International Cooperation Programme ICP Forests was implemented, which has been investigating the condition of forests throughout Europe since 1985. In 1985, Switzerland carried out the first regular Sanasilva inventory. This was done on the one hand to fulfil the terms of the pan-European agreement under ICP Forests, and also because politicians, researchers and the general public were asking for reliable data on the condition of the forest and how it was changing. Since then, WSL has been recording the health of trees in Swiss forests annually on around 49 sample plots, based on crown condition (fig. 3), mortality and other stress indicators.

Fig. 3. Continuous measurement series show the overall trend of increasing crown defoliation since 1990: The deterioration in crown condition is particularly pronounced after extreme storms (Lothar 1999) and hot summers (2003, 2018). Such developments may trigger a reassessment of the future of the beech in central Europe, for example.

Long-term forest ecosystem research (LWF)

At the same time, national studies began to investigate the effect of air pollutants on forests. From the mid-1990s, such intensive monitoring of ecological processes was extended to the whole of Europe as part of ICP Forests. In Switzerland, WSL carries out the long-term forest ecosystem research (LWF) on 19 research plots (Level II in the European ICP Forests network). Around 25 million measurements per year are recorded, with roughly 50 sensors and collectors per site (fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Overview of the types of measurement and sensors on the LWF research plots. Diagram: LWF 2022

Fig. 5. Negative pressure is applied to the lysimeter to extract soil water on the LWF site in Vordemwald. Photo: M. Schmitt (WSL)

The combination of automatic measurements, collectors, periodic sampling and visual surveys provides a better understanding of the relationships between environmental influences and their effects on the forest.

As part of ICP Forests, several hundred experts have been conducting annual forest condition surveys (Level I) on around 6000 sites across almost all of Europe for 40 years, as well as intensive surveys (Level II) on around 700 sites for the last three decades. The surveys today go beyond the original focus and cover topics such as climate stress, nitrogen deposition and biodiversity. Due to the large number of sites and the length of the time series, this international cooperation provides insights that "normal" 3–4 year studies are generally unable to achieve. The results also form the basis for negotiations on air pollution control measures or for climate-related considerations, such as the elaboration of recommendations for a future-oriented selection of tree species.

Climate change and stress factors: what makes forests vulnerable?

Air pollutants

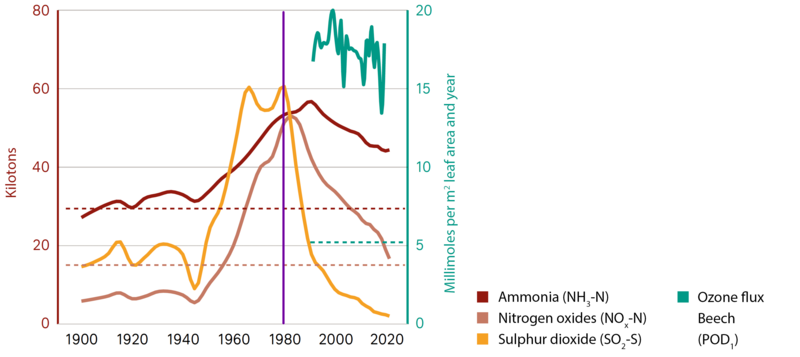

The sharp decline in sulphur immissions since the 1990s shows that political measures are working. However, the reduction target for nitrogen immissions has not yet been achieved. The immissions often remain above the critical values on the Swiss Central Plateau and in the foothills of the Alps. Soil acidification has slowed down again for the most part, but nitrate levels in the soil water are still high in some cases. Particularly affected by this are sensitive forests, where material cycles are thrown out of balance. Despite a slight downward trend, ozone concentrations remain above critical levels. Ozone is the only air pollutant that causes specific visible symptoms on the leaves of deciduous and coniferous trees, which are observed every summer. Ozone also leads to significant growth losses.

Fig. 6. Emissions of air pollutants in Switzerland from 1900 to 2020 and development of the ozone flux (POD1) for beech trees (green). The dotted lines correspond to the targets set out in the [Swiss] Federal Council's 2009 Clean Air Concept for NOx and NH3 and the critical load values for ozone defined by the UNECE.

Temperature, drought, extreme events

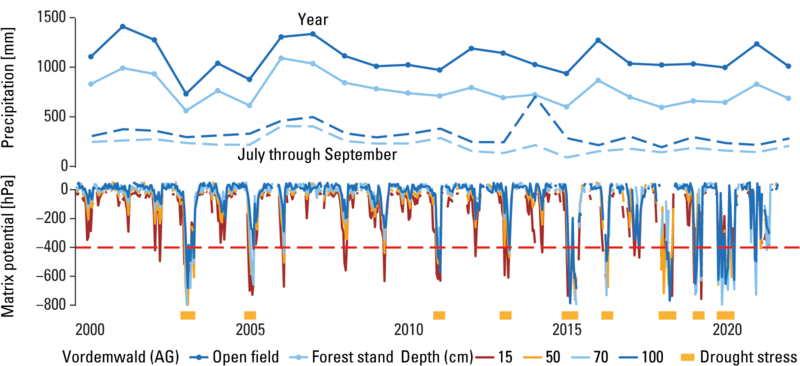

Increasing summer drought is the dominant climate stress factor. Years with water scarcity or longer periods of drought stress have increased noticeably over the last few decades. On selected LWF plots, the precipitation (open land), water throughfall into the stand (crown dripline) and the water availability in the soil are recorded (fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Climate-relevant water flows on selected LWF plots. The figure shows selective measurements in the soil-plant system: Precipitation in open land and in the stand (under the canopy, top), soil moisture and water availability at different soil depths, quantified via the matrix potential (Ψm, suction tension in hPa).

If water becomes scarce, trees have to build up a greater negative water potential in order to absorb the remaining water bound to fine soil particles. The so-called matrix potential is a measure of the binding force of the water to the soil matrix. If this falls below around –400 hPa, trees react to the onset of water stress by adapting physiologically to reduce water consumption, for example by closing their stomata or shedding their leaves early.

A strongly negative matrix potential (with pronounced water deficit) and a dry, hot atmosphere at the same time can further increase the pressure: Low relative humidity or a high vapour pressure deficit (VPD) increases evaporation via the leaves and, in combination with a strongly negative matrix potential, can interrupt water transport in the trunk through the xylem - resulting in cavitation (embolism formation) and direct damage to the trees.

Remote sensing and real-time data

Technological advances in recent years are promising and may enable an expansion of forest monitoring possibilities.

With remote sensing data such as the Photochemical Reflectance Index (PRI), which is collected using drones, aeroplanes or satellites, early detection of drought stress is now possible. Initial tests on LWF plots show that the PRI is suitable as an effective stress indicator at both tree and ecosystem level.

At the other end of the scale, point dendrometers record trunk growth and the water deficit in the tree in real time. A key finding from these long-term measurements is that it is not primarily the length of the growing season that determines the productivity of trees, but the number of growing days actually used.

This combination of long time series using classical methods with new “remote and near measurements” provides a differentiated picture of growth dynamics under changing climatic conditions.

Biodiversity as a buffer

The long-term studies on the LWF plots show that the ground vegetation is changing, both as a result of higher nitrogen availability and changes in light conditions due to management practices. The LWF plots are being used for further research. It has for example been shown that the composition of soil organisms - especially ectomycorrhizal fungal communities - plays an important role in nutrient cycling and carbon storage in forests. Genetic analyses have shown that the structure of these fungal communities changes from a nitrogen input of 4 kg per ha and year and that it has a significant influence on tree growth and the carbon stocks in the biomass.

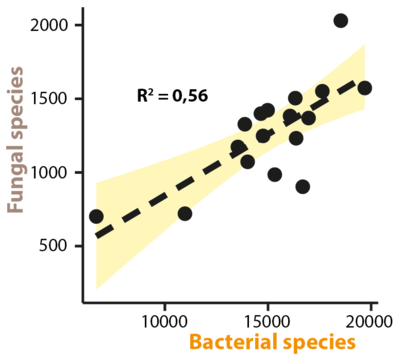

In addition, these surveys on LWF plots indicate that fungal and bacterial diversity in the forest soil are linked on a site-specific basis (fig. 10): where there are many species of fungi, there are also many species of bacteria. The numbers of fungal and bacterial species can also be high in areas with only a few tree species. This relation is relevant for forestry practice because both groups perform key soil functions – in the nutrient cycle, for example, in humus formation or in defending against pathogens. High microbial diversity strengthens soil health and increases the resilience of the forest to drought stress and other risks.

Such results indicate that diverse microbial communities can provide functionally important buffering capacities against environmental stress factors – for example with regard to nutrient retention and water balance.

The bottom line

Four decades of forest ecosystem research show that changes in the forest often take place slowly, their causes and interactions are complex - and their consequences are long-term. This makes continuous, systematic measurement series that go beyond mere snapshots all the more important. Today, the LWF data provide an indispensable basis for identifying critical stress thresholds, understanding ecological relationships and deriving appropriate forestry measures and political measures. They show that resilience is not only a question of tree species, but also depends on soil processes, biodiversity and environmental stress factors.

Sustainable forest management therefore requires thinking in terms of networks: site, climate, species selection, technology and soil health must be considered together. The findings from long-term research help us to understand - and protect - tomorrow’s forests today.

Translation: Tessa Feller