Fig. 1. A point dendrometer consists of an electronic sensor mounted on a carbon frame that measures the change in stem radius every 10 minutes. Changes in stem thickness occur mainly in the elastic tissue of the bark, with new cells forming in the cambium. Photo: Roman Zweifel (WSL)

A tree that grows in the dark – what sounds absurd at first is actually based on scientific data. The long-term measurements of the nationwide TreeNet monitoring network in Switzerland show that trees mainly grow at night. This statement is made possible by high-precision point dendrometers that measure the stem radius with micrometre accuracy – every ten minutes, around the clock. The measurements not only provide data on growth, but also on the water balance of the trees. This allows us to deduce how tree species cope with drought generally, and which species are particularly sensitive or robust. These findings could change the way in which the effects of climate change on forests are assessed.

The TreeNet network

TreeNet is an environmental monitoring network for measuring tree growth and drought. It is embedded in an international network of environmental monitoring systems (LWF, ICOS, eLTER, ICPForests) and is supported by institutions such as the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research WSL, ETH Zurich, the University of Basel, the University of Zurich, the Institute for Applied Plant Biology IAP in Witterswil and the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment FOEN.

Fig. 2. Point dendrometer.

Photo: Roman Zweifel (WSL)

Since 2011, TreeNet has been continuously measuring the stem radii of more than 600 trees at about 70 sites in Switzerland. So-called point dendrometers are used for this purpose – sensors that deliver micrometre-precise data every ten minutes.

Changes in stem radius are an indication either of cellular growth (increase in wood and bark), or stem shrinkage or expansion caused by an imbalance between water loss (transpiration in the leaves) and water uptake (in the roots).

Three central parameters for tree growth can be derived from this data:

- Stem growth: growth through cell formation

- Tree water deficit (TWD): current water deficiency in the elastic stem tissue

- Maximum daily stem shrinkage (MDS): indicator of a tree’s water storage capacity

The radii of tree stems shrink and expand under the influence of water stress within a range of 1–300 micrometres per day. These water-related fluctuations are overlaid by the growth of wood and bark cells, which averages around 5–30 micrometres per day.

At the same time, soil and climate data are recorded on these sites, including air temperature, humidity and soil water potential, which are linked to the values for the changes in the tree. All data flows automatically into a central TreeNet database, where it is analysed using standardised methods.

Why trees grow at night

The analysis of over 57 million measurement points in a large TreeNet study shows that trees mostly grow at night. The reason for this lies in the water balance of the plants. During the day, water evaporates through the stomata of the leaves (transpiration), leading to a decrease in the turgor (internal pressure of the cell) in the cambium (cell-forming tissue). Growth stops. Only at night, when the evaporation decreases and the tree once more absorbs more water than it loses, does the pressure in the cambium increase - and cell division and cell elongation become possible.

The decisive factor for tree growth is not so much how long the annual vegetation period lasts, but how many hours or days within this period can actually be used for growth (fig. 3).

These “growth hours” depend not only on the availability of soil water, but also heavily on the humidity of the air - or more precisely on the so-called vapour pressure deficit (VPD), which is a driver of transpiration. The VPD is lower at night (or the air humidity is higher) – a major reason for nocturnal growth.

Visualising drought stress in real time

The sensors not only provide data on growth, but also on drought stress. When a tree stem shrinks, there is a water deficit. TreeNet data makes it possible to identify such stress phases across the whole of Switzerland. The treenet.info platform publishes maps updated on a daily basis that show which trees are suffering from drought where, and where trees are growing and how vigorously (fig 4).

Fig. 4. Current cumulative annual growth, current daily growth and current water deficit (drought stress) of all trees on a site on 8 July 2025. Source and current graphics: treenet.info

For forestry practitioners, this information can be used together with other indicators to develop early warning systems for vitality loss, site problems for certain tree species, or an increased risk of forest fires (treenet.info/nowcasts). Agriculture and the public can also benefit from this early detection, as forest trees provide an integrative, largely uncompromised picture of drought in the air and soil of a region and thus give an indication of where the drought is severe, regardless of agricultural cultivation and management.

Growth and water management

Tree species differ greatly in how they respond to different environmental conditions. A key parameter is the so-called maximum daily stem shrinkage (MDS), an indicator of the water storage capacity in the stem. Within a species, higher MDS values indicate greater growth. In a comparison between species, however, species with high MDS values tend to grow less - presumably because large storage capacities are more difficult to replenish when water is scarce.

Ultimately, three factors contribute significantly to the annual growth of a tree species: how many hours per year it can grow; how much it grows on average per day; and how large its water storage capacity is (fig. 5). The number of growth hours is strongly determined by the local moisture conditions in the air and soil and can vary from year to year, while the other two factors are largely determined by the tree species and are less dependent on environmental conditions.

Fig. 5. The growth potential of our tree species or their average annual growth is characterised by the number of growth hours per year (the higher, the greater), the growth rates per day (the higher, the greater) and the water storage capacity (the higher the water storage capacity, the lower the growth potential). Source: treenet.info

There is also a delay in the reaction of trees to the conditions of previous years - the so-called legacy effect. This is linked to the storage of carbon and nutrients , which build up or are reduced over years. Closely related to this is the ability of trees to form new, adapted structures each year, such as more roots, more conducting vessels, or smaller leaves.

In a recent analysis of TreeNet data, the Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and the silver fir Abies alba) proved to be particularly productive, with up to four times more usable growth time than the downy oak (Quercus pubescens), for example. However, the downy oak also grows in relatively dry soil provided the air humidity is high enough, whereas species such as the silver fir require constantly moist conditions: Tree species that are suited to their site can make better use of their growth reserves.

Regional map analyses also show clear differences in the long-term average drought stress: The highest levels occur in Valais and on individual sites in northern Switzerland, the lowest on the Swiss Plateau (fig. 6). However, it is not only the regional climate that is decisive for growth, but also the choice of tree species at the respective site.

New perspective on carbon dynamics in forests

The fact that trees only grow during a narrow time slot of just a few hours within the 24 hours of a day and thus only for a limited time over the entire vegetation period (totalling around 15–30 days depending on the tree species) provides a new perspective on carbon dynamics in forests: Since carbon gain (photosynthesis during the day, entire vegetation period) and carbon consumption (growth during the night, only during approx. 2–3 months) take place at different times of the year and day, these two processes also react differently to the prevailing weather conditions. Climate-forest development models used up to now, on the other hand, are based solely on knowledge derived mainly from annual average growth values, and thus do not take into account the processes that occur at different times of the day. These findings could change the way in which the effects of climate change on forests are assessed, especially when it comes to long-term predictions of carbon storage in forests under increasingly dry conditions.

From point to entire area

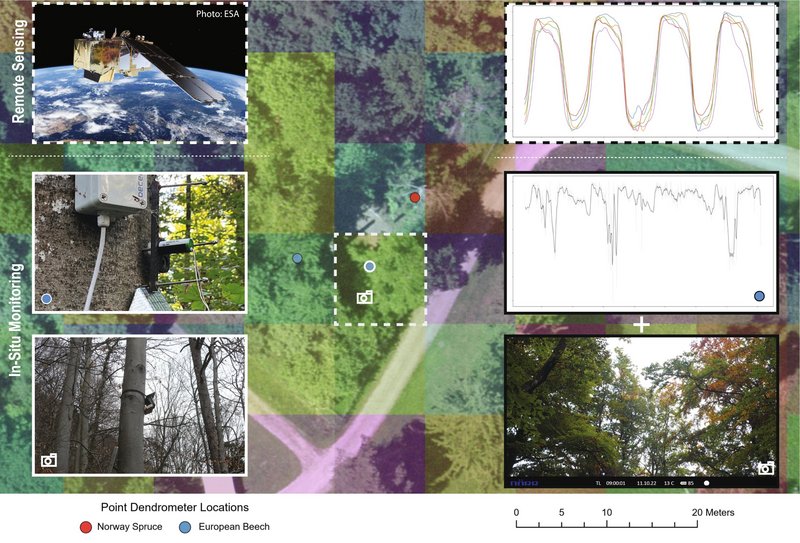

TreeNet provides precise data on the tree water deficit on individual sites. But how can this information be transferred to the entire area? New research shows that this is possible (fig. 7): on the one hand through the correlation between the change in stem radius data and air and soil conditions, and on the other hand by combining TreeNet measurement data with satellite observations (Sentinel-2). Both approaches have the potential to transfer drought stress signals from individual measurement sites to entire forest regions.

Fig. 7. Example of a Sentinel-2 time series in comparison with a point dendrometer tree water deficit time series. A Sentinel-2 grid with a resolution of 10 m is superimposed on an aerial photograph of the same location (Swisstopo, 2024) and compared with the tree data measured on the ground. Source: Bloom et al. (2005)

Remote sensing indices such as NDVI, CCI and NDWI are used to capture large forest areas from satellite images with a high spatial resolution on a weekly basis. Although they cannot yet fully reflect daily fluctuations in tree water deficit, monthly aggregations already provide reliable estimates. These can facilitate certain management decisions, e.g. the planning of thinning measures or the selection of tree species under climate change conditions.

The bottom line

The TreeNet data provides valuable information for forestry practice and forest ecology research. They permit objective assessment of tree vitality in real time and help to identify suitable tree species on the right site - particularly with regard to drought tolerance. TreeNet permits:

- comprehensive monitoring of drought stress and the growth of forest trees,

- the analysis of species-specific differences,

- climate-smart forest management by allowing for the targeted planning of measures with adapted tree species

and - the identification of vulnerable stands - for example through species-specific relationships between remote sensing data and tree water deficit.

Further scientific publications

Etzold S., Sterck F., Bose A.K., Braun S., Buchmann N., Eugster W., … Zweifel R. (2022) Number of growth days and not length of the growth period determines radial stem growth of temperate trees. Ecol. Lett. 25(2), 427-439. doi.org/10.1111/ele.13933

Zweifel R., Sterck F., Braun S., Buchmann N., Eugster W., Gessler A., … Etzold S. (2021) Why trees grow at night. New Phytol. 231(6), 2174-2185. doi.org/10.1111/nph.17552

Zweifel R., Bachofen C., Basler D., Braun S., Buchmann N., Conedera M., … Walthert L. (2025) Wachstum und Trockenstress: physiologische Charakterisierung von Schweizer Waldbäumen. Schweiz. Z. Forstwes. 176(2), 99-105.

Bloom C.K., Koch T.L., Meusburger K., Zweifel R., Walthert L., Etzold S., … Baltensweiler A. (2025) Towards near real-time drought stress assessment in Europe's temperate forests – comparing remote sensing time series with continuous in-situ tree-level measurements. Ecol. Indic. 177, 113757 (15 pp.). doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2025.113757

Translation: Tessa Feller