Forests are complex, living socio- ecological systems. Those who manage or steward them constantly navigate between planning and unpredictability. This is where Simon Reinhold, Olef Koch, Andreas Schweiger, and Roderich von Detten come in: In their article in Forest Ecology and Management, they present the idea of no longer seeing uncertainty as a disruption, but as an integral part of modern, adaptive forestry.

The article provides the theoretical foundation for the research project “reSyst” at the Universities of Freiburg and Hohenheim. In this project, the actual possibilities of forest district managers to “steer” forest ecosystems in the face of growing uncertainties is examined. The findings are used to derive concrete recommendations for dynamic forest management.

Instead of trying to reduce uncertainty through elaborate forecasts or risk distribution, the authors propose a different perspective: the “License to Fail” – the conscious permission to allow errors and use them as learning opportunities.

Planning vs. Chaos: The Contradiction in Forestry

Forestry relies on planning. Trees take decades to become usable, and forest managers must consider the far future. At the same time, forests are increasingly understood as complex, adaptive systems – systems that continuously change and whose development is barely predictable.

On top of that, societal demands on forests are constantly changing. Climate change, globalization, and new demands on ecosystem services increase uncertainties even further. Forest managers repeatedly face so-called “wicked problems” – problems without perfect solutions, which must always be addressed under uncertainty.

This contradiction – long-term planning on one hand, chaotic and hard-to-predict developments on the other – is the starting point for the thoughts on a “License to Fail.”

Resilience as a Response – and Its Limits in Practice

The response to increased uncertainty is often the claim that forests must become more resilient. Resilience in this context refers to the ability to withstand disturbances such as droughts, storms, or pests and swiftly recover after those impacts.

However, applying the concept of resilience in practice remains challenging. Usually, only one type of resilience is strengthened – for example, resistance to drought. Also, resilience often implies the preparation of the forest for the challenges of the future, thus assuming specific future scenarios that may never occur. The result: uncertainty is reduced rather than truly embraced.

Achieving general, all-encompassing resilience is hardly possible. Therefore, a different perspective is gaining importance: not only should forests become more resilient, but so should management. What matters is how decisions are made, how we learn, and how we deal with uncertainty.

Learnings from the Management Literature – Quicker Reactions, better adaptations

While forest sciences still rely heavily on forecasts, other disciplines are already further ahead in dealing with uncertainty. Especially more general management literature gives more advice on dealing with irreducible uncertainty. These insights can also be put to use in forest management, for example:

- Process new information quickly and integrate it into decisions in a timely manner. Good information flow also serves as a basis for productive discussions with colleagues, scientists, and stakeholders.

- Respond better to surprises instead of trying to eliminate them in advance.

- Buffering silvicultural risks through diverse forests can have a flipside: a forest managed with the motto “the more diverse, the better” may also lead to more complicated management and slower adaptation. Forest potentials must be recognized and developed without leading into dead ends.

This allows for a shift of perspective: forests should not be seen as static entities to be stabilized as much as possible. Moreover, it is not helpful to focus on distant future goals during times of major change. Instead, forests should be understood as complex systems in constant transformation.

Experimenting, Learning and Adapting

Understanding forests as systems of constant change consequently requires an adjusted management. Instead of sticking to rigid plans, forest management needs experimentation, continuous learning, and flexible decision-making.

This also involves a new mindset: uncertainty is not a mistake to be eradicated. It is a integral part of forestry – especially in multifunctional, close-to-nature forest management which is prevalent in Germany.

This means:

- Elements based on trial and error should become more popular in forest management.

- Organizations need awareness that uncertainty is permanent.

- Success is measured not only by short-term results but also by how well one adapts to changing conditions.

In this manner, a dynamic process can be created that develops both forest and management further simultaneously.

Proposal 1 – Observe Ecosystems Over Long Time Periods

A key to handling uncertainty better is a careful observation of ecosystems. Forests are constantly changing – what works today may fail tomorrow.

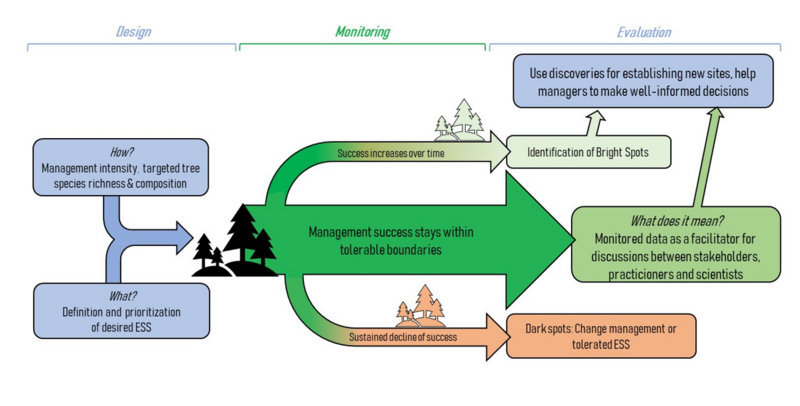

Fig. 3: Observe ecosystems over long time periods. Made in Biorender by Andreas Schweiger https://biorender.com/i98l882

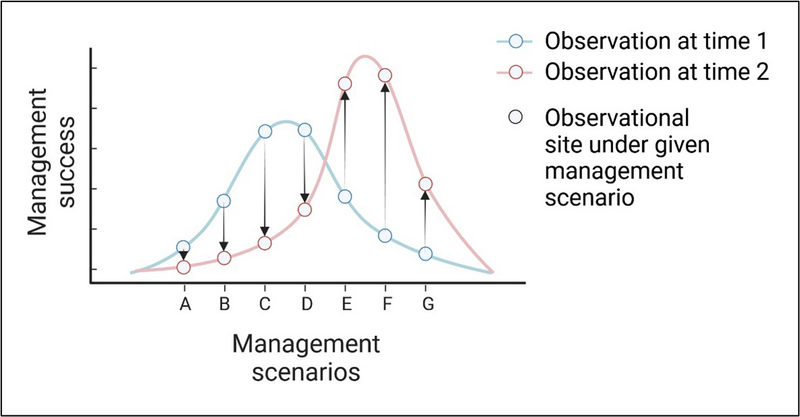

Long-term measurements illustrate this well (Fig. 3):

- Imagine several forest plots (A–G) managed according to specific guidelines.

- Initial success is measured, for example, in biodiversity, water retention, or economic value.

- In fixed intervals, measurements are repeated.

When observed over longer time frames, a management approach that was very successful initially may perform worse the next time simply because external conditions have changed.

The advantage of such observations is clear: they show that forests and environmental conditions are constantly changing. Management should therefore not be seen as a one-time decision but as a process that must continually prove itself.

Proposal 2 – Learn Through Experiments

The process is relatively structured (Fig. 4):

- Planning (Design): Determine which type and intensity of management will be tried and which ecosystem services are prioritized.

- Observation (Monitoring): Implement the measures over a long period and carefully track forest development.

- Evaluation: Ask the central question: What does this mean for our future management?

Crucially, a management approach that works in one situation may suddenly fail under different conditions. Experiments make this dynamic visible and provide learning opportunities.

It is therefore crucial to rethink organizational structures in forestry: while knowledge is currently transmitted “from research and administration to the field,” embracing uncertainty requires knowledge to be developed collaboratively. Forestry organizations must adapt to a constantly changing world, moving toward entities that openly address uncertainty and use it as a learning opportunity – improving communication both bottom up among hierarchies and laterally among colleagues.

Between Planning and Change – Forestry as a Process

Forest management inevitably moves between planning and unpredictability. Instead of viewing uncertainty as a disruption, the “license to fail” opens up a new perspective: mistakes and surprises become impulses for learning and adaptation. Observation, experimentation, and decisions that allow further decisions or actions to build on them make it clear that successful forestry does not pursue a rigid goal, but is an ongoing process—in constant dialogue between the forest, management, and knowledge gained. Especially in times of increased uncertainty, forestry must be understood as true management: a matter of manoeuvring and continually weighing between several imperfect solutions.