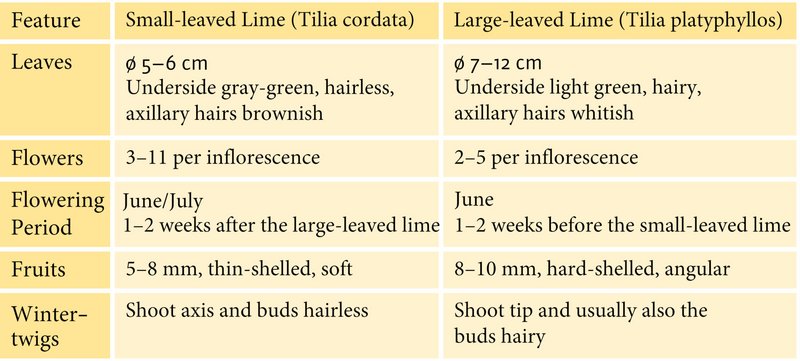

In Central Europe, two lime species are native: the small-leaved lime (Tilia cordata) and the large-leaved lime (Tilia platyphyllos). Both belong to the mallow family (Malvaceae) and share several morphological features, including heart-shaped leaves with serrated margins and an alternate arrangement along the twig. The key characteristics used to distinguish these two species are shown in Figure 1.

Both lime species produce leaf litter that decomposes readily and has a favorable C/N ratio, making them tree species known for improving humus formation and soil quality. Their wood is also very similar: pale, diffuse-porous, lightweight, uniform in texture, and soft, with excellent workability. For this reason, limewood has long been valued in carving and sculpture, as well as in woodturning. It is also used as secondary (non-visible) wood in furniture, and for drawing boards, pencils, and toys.

Site Requirements and Distribution in Bavaria

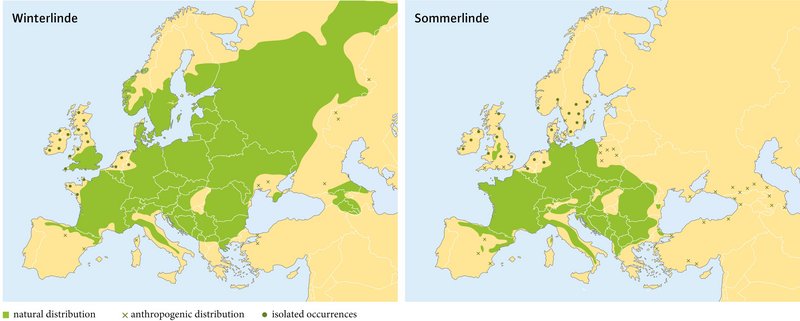

Both lime species are more warmth-loving than beech and are considered climate-resilient tree species. However, the large-leaved lime has higher site demands than the small-leaved lime: it prefers fresh, nutrient-rich, and winter-mild locations, and it avoids very dry conditions. It thrives best in block and ravine forests of the hill country and the low mountain ranges. The small-leaved lime, in contrast, is characteristic of oak mixed forests and also colonizes drier and more nutrient-poor sites. Both species coppice very well, which is why they were strongly favored in historical coppice-with-standards management.

Lime trees occur scattered throughout many forests in Bavaria. Particularly vigorous individuals can be found in the mixed broadleaf forests of the Franconian Plateau. Notable lime populations also occur in the Franconian Triassic Hill Country, the Franconian Keuper region, the Franconian Jura, the Upper Palatinate basin and hill country, and the alluvial forests of southern Bavaria. The large-leaved lime, which has a narrower ecological amplitude than the small-leaved lime, is found mainly in ravine forests and steep-slope woodlands of the Bavarian low mountain ranges and the Bavarian Alps.

Humans and the Lime Tree – A Long-standing Relationship

Lime trees can live to a very old age — reportedly up to 1,000 years. As village, court, peace, and courtyard limes, they have accompanied humans and their societies for centuries. A special feature is the remaining dancing limes in Franconia and southern Thuringia. Notable examples include the dancing lime in Limmersdorf, where people still dance in the tree’s crown during the “Lindenkerwa” festival, and the Effeltrich lime. In Germany, over 1,100 towns derive their names from the lime tree.

While the oak symbolized strength, durability, combativeness, and masculinity, the lime tree was associated with warmth, security, family, and femininity. The village, courtyard, and court limes found in villages, towns, and open fields are mostly large-leaved limes.

Lime Trees and Their Wildlife

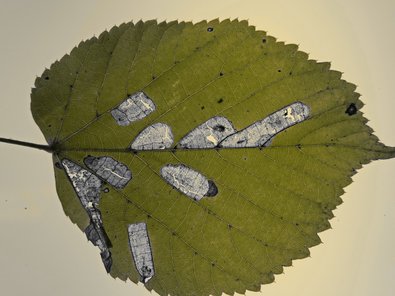

Over 200 phytophagous insect and mite species have been recorded on the two lime species native to Central Europe. The most species-rich groups are large moths (77 species), micro-moths (26 species), and beetles (52 species). Typical lime-associated species include the lime hawk-moth (Fig. 6), the lime tortrix moth, and the lime jewel beetle. In spring, large aggregations of the conspicuously black-and-red firebugs are often found under lime trees. Since 2004, two new insect species have been observed on lime trees in Germany: the linden leaf-miner moth (Phyllonorycter issikii), originating from East Asia (Fig. 4), and the Mediterranean mallow bug or lime bug (Oxycarenus lavaterae). Before overwintering, the lime bugs gather in often huge colonies on thick branches and trunks (Fig. 5). To date, neither of these species is known to cause economic or ecological damage.

Popular with Bees and Beekeepers

All lime species of the genus Tilia are important forage plants for both wild and honey bees, providing nectar as well as pollen. Lime flowers are especially attractive to flower-visiting insects (Fig. 7). Honey bees, wild bees, hoverflies, beetles, and butterflies readily feed on the nectar.

Silver Lime – Better Than Its Reputation

The silver lime (Tilia tomentosa), widespread in southeastern Europe, is primarily planted in urban areas in Central Europe and could gain importance in native forests with ongoing climate change. For many years, its planting was discouraged because its nectar was thought to be toxic to bees and bumblebees. Research now shows that the cause of dead insects under silver limes is not the nectar, but a lack of food.

Silver limes bloom later in the year than the small-leaved and large-leaved limes, at a time when few other plants are flowering, especially in cities. This makes the flowering silver limes highly attractive to bees and bumblebees. However, the nectar supply is not unlimited, and during high foraging pressure, it is quickly depleted. As a result, bees, bumblebees, and other insects may stagger to the ground exhausted and starve. To improve the food supply for insects and extend the foraging period, it is therefore sensible, particularly in urban areas, to plant more silver limes.

The Medicinal Effects of the Lime Tree

In terms of pharmacologically relevant compounds, the native lime species are very similar and both can be regarded as medicinal plants. The selection of the lime as the German medicinal plant of the year 2025 primarily highlights the healing properties of lime blossoms (Fig. 7). These are mainly used to prepare tea. Their main active ingredients are flavonoids, mucilages, and essential oils. Traditionally, lime blossom tea was used as a classic sweat-inducing tea to treat colds and coughs.

Summary

Until now, both native lime species have played a relatively minor role in forestry. With climate warming, the importance of lime trees — including the southeastern European silver lime — is expected to increase in our forests and urban green spaces. Lime species are well adapted to rising temperatures and are considered robust trees for climate change. With their easily decomposable leaf litter and shade tolerance in their juvenile stage, they can contribute to the development of future-proof mixed forests and help enhance biodiversity in our woodlands. Foresters, forest owners, and nature enthusiasts should therefore also promote lime species in our forests.