The dry conditions of recent years show how sensitively forests react to extreme climate events. Summer droughts influence growth and chemical processes in trees. This can in turn affect the relationships between trees and other organisms such as herbivorous insects. An understanding of the long-term effects of these interactions on forest ecosystems is essential for the development of forest management strategies that are able to meet the challenges of the future.

Trees and herbivores: a complex interplay

Herbivorous insects play a central role in forest ecosystems. They can be grouped according to their feeding habits into so-called “feeding guilds”, such as leaf-eating insects like butterfly larvae, or sap-sucking species like aphids. These two groups react in different ways to drought stress in the trees: while sap-suckers often prefer stressed plants, leaf-eaters thrive better on unstressed trees. These reactions are partly due to changes in the chemical composition of the leaves that are caused by drought.

The beech as a keystone species

The common beech (Fagus sylvatica) is the dominant deciduous tree species in central Europe, and provides a habitat and food for many organisms. Its leaves contain innumerable chemical metabolites, with various functions. Primary metabolites are necessary for growth and energy balance, while specialised metabolites serve for example to defend against predators. Drought stress can significantly alter this chemical profile and thus have a lasting impact on the interactions between the beech and insects.

In the summer of 2018, many beech trees reacted to extreme drought stress by shedding their leaves prematurely, while other trees on the same sites showed no visible symptoms of stress. This phenomenon provided a unique opportunity for studying the long-term consequences of drought.

Focus on chemistry and feeding damage

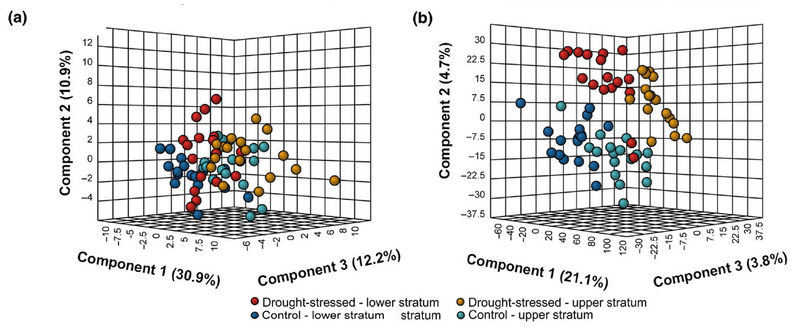

A comparison of the chemical profiles of the leaves of trees previously subject to drought-stress and those of unstressed trees shows clear differences (see fig. 5). To detect differences within the tree crown, leaves from both the sun-exposed and shaded lower parts of the crowns were analysed.

Changes over several years

Drought stress left no long-term traces in the primary metabolites of beech leaves (fig. 5a). By contrast, the profiles of the specialised metabolites differed significantly between stressed and unstressed trees - not only in the year directly after the drought, but also in the following year (fig. 5b).

Fig. 5. Score plots of a partial least squares discriminant analysis of (a) the primary F. sylvatica metabolome and (b) the specialised metabolome of leaves from the upper and lower crown stratum of previously drought-stressed and control trees for the second year after the drought. Each dot represents a leaf sample of 30 pooled leaves.

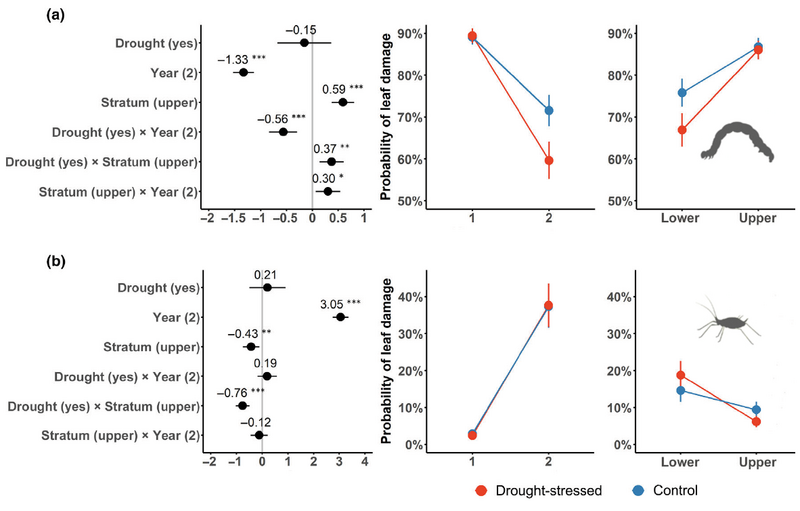

Feeding damage caused by leaf-eating insects occurred with similar frequency in the first year. In the second year, however, the probability of such damage decreased by 10 % in stressed trees, especially in the shaded areas of the tree crowns (fig. 6a). In the case of sap-sucking insects, there were hardly any differences between the stressed and non-stressed trees, but the drought stress did influence the probability of finding sucker damage differently depending on the crown stratum (fig. 6b).

Fig. 6. Estimates and line plots illustrating the effects of previous drought stress, year after the drought event, crown stratum, and their two-way interactions on the probability of finding Fagus sylvatica leaves with (a) eating or (b) sucking damage. Mean effect sizes (± standard error) of the various factors, including interactions (left). Factors have a significant influence if they do not intersect with the red zero line. Mean values (± standard error) of leaf damage probability on previously drought-stressed and control trees one and two years after the summer drought (centre) and in the sun-exposed and shaded crown (right).

P-values: * < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001.

The influence of drought stress varied significantly depending on the position in the crown: in the shaded part of the crown, the probability of visible damage caused by leaf-eating insects decreased significantly (fig. 6a), while the probability of damage caused by sap-sucking insects increased slightly (fig. 6b). In the sun-exposed crown area, there were hardly any differences in leaf damage between drought-stressed and non-stressed trees. These patterns indicate that drought stress does not affect the entire tree crown evenly.

Significance for ecosystems and forestry

The long-term effects of drought events on ecosystems are complex and extend far beyond tree-herbivore interactions. If chemical changes in the leaves of the trees manifest themselves over the long term, this has potential consequences for entire food chains. The presence of fewer leaf-eating insects can mean that specialised predators such as birds or other insects find less food, which in turn affects the population development of these species. At the same time, increased sucking damage to stressed trees can impair their ability to regenerate.

The changed feeding patterns are also relevant for the nutrient cycle in forests. If less leaf mass is broken down, for example, this can change the availability of nutrients in the soil and thus influence the growth conditions for subsequent generations of trees. In the long term, such effects can lead to a shift in the tree species composition in forests.

Specific courses of action

Measures focussing on the short-term consequences of drought events are already largely established. They include the targeted removal of weakened or dead trees, sanitary felling to contain secondary pests such as bark beetles, and preventive measures to avert forest fires. In addition, young trees are watered selectively during critical phases, and the soil structure is protected by appropriate maintenance measures.

In the long term, however, additional strategies are needed to manage forests in such a way as to make them climate-resilient. Monitoring programmes should be expanded to provide a more differentiated view of the long-term development of tree health. Indicators such as the chemical composition of the leaves could possibly provide early warning signs of creeping losses in vitality or changes in browsing risks - even before crown damage becomes visible. This would allow critical developments to be recognised at an early stage and silvicultural measures to be better planned.

Researchers need to investigate more closely how different tree species react to repeated drought events, and how their resilience can be improved in the long term. Simulations and modelling can help to improve the prediction of future scenarios under worsening climate conditions. They provide a valuable basis for decision-making aimed at increasing the resilience of forests to climate change - for example for the selection of drought-adapted tree species, the composition of stable mixed stands, or the timing of silvicultural measures.

The bottom line

Extreme drought events permanently change the balance in forest ecosystems. Long-term observations such as these are crucial for creating more resilient forests, and for mitigating the consequences of climate change.

Translation: Tessa Feller