“Hollander” was the name given to stately fir or spruce trunks which, because of their extraordinary dimensions - up to 30 m long and 40 cm thick even at the thinner end - were exported to the Netherlands via the Neckar, Main, Moselle and Rhine rivers. With its naval and urban architecture and worldwide trading network, Holland was an emerging power and the largest manufacturing region in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, exerting a tremendous pull on raw materials - one that would be almost unimaginable today.

From the 17th to the 19th centuries, “Holländerholz” was an established term in forestry in Germany (Fig. 1). What was meant was timber exported via the Rhine to the Netherlands. In those days, Holland and England needed immense quantities of timber, not only for the expansion of their navies and merchant shipping fleets, but also for hydraulic and civil engineering projects. The demand was met with timber from Switzerland and the Black Forest, and from the low mountain ranges of Franconia and the catchment area of the River Main and its tributaries in Bavaria, especially from the Frankenwald forest, the Bamberg Hauptsmoorwald forest and the Spessart forest (see box below).

Holland - Europe’s economic motor

Holland is a country almost devoid of forests, and without its own raw materials. It does not have changes in elevation to generate energy and thus cannot harness water power to drive classical mills. No forest, no raw materials, no hydropower: three of the key requirements for economic prosperity in the Middle Ages were thus missing in Holland, unlike the situation in the Oberpfalz (“Upper Palatinate”) region, for example, where a combination of timber, mineral resources and water power allowed the region to flourish economically.

However, Holland's location on the sea and River Rhine is very favourable, making it an ideal transport hub. The increase in shipping traffic from the 16th century onwards meant that markets were opened up worldwide, and as a key raw materials and sales market, central Europe was easily accessible via the Rhine. As wind could also be relied upon to blow on the coast, the lack of water power could be compensated for by windmill technology, which had been further developed in Holland.

Raw materials in, value added goods out

From the Middle Ages onwards, Holland imported wool on a large scale from England, and then wove it on mechanised looms in the cities into fabrics that could be sold throughout Europe. Holland gradually developed over the 16th and 17th centuries into the most important manufacturing landscape and trading hub in Europe.

This booming region on the Lower Rhine traded in wine from the Mediterranean, furs from Russia, and wood from Scandinavia and the Baltic. Because there was a lot of money in circulation, art also flourished in this prosperous region of Europe. This is shown by the highly productive, large painting workshops of Rembrandt and Rubens.

When goods ceased to reach western Europe via the Silk Road, due to the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and constant conflicts with the Ottoman Empire, the Italian city-states lost their trade monopoly on the Asian goods they had up to then imported from the Levant. It was only when the Portuguese had circumnavigated Africa and found their way to India (Vasco da Gama, 1498), and the Spaniards (Christopher Columbus, 1492) had discovered America, that a global store of raw materials and an equally large sales market were opened up for Europe. Maritime trade routes therefore became increasingly important in the 16th century. It was now the states on the edge of Europe, with direct access to the Atlantic, that had the advantage. They set up trading companies for the East Indian trade. The Dutch East India Company - founded in 1602 - had branches on all continents, and traded in goods and raw materials from all over the world: New Amsterdam (today: New York), Surinam, Java, South Africa.

Shipbuilding and harbour construction

In 1660, Europe had around 20,000 merchant ships, of which as many as 16,000 were owned by the Dutch. They built them primarily for themselves, but exports to the emerging England were also booming (Fig. 2). Around 4000 150-year-old oaks were needed to build one sailing ship. A warship with 100 cannons required 5000 oaks. As late as 1800, 5000 Spessart oaks were transported as ballast on a raft from the Frankenwald forest to Holland, and used to build an English warship.

But large quantities of timber were not only needed for shipbuilding and shipyard facilities. Driven piles were also needed for hydraulic engineering, harbours and canals. For the foundations of buildings on boggy ground, piles that had to be at least 11 m long were used. Whole districts of Amsterdam and other Dutch cities rest on the many millions of wooden piles that have been rafted in over the centuries. And a lot of wood also went into house construction, the furnaces, and for use in various trades. Long beams were needed for the windmills, with their paddles of up to 9 m in length. Pines from the Hauptsmoorwald forest have few knots, hardly warp, and are particularly suitable for the paddles or blades of Dutch windmills.

Windmills

Holland lacks slopes, so water mills with reservoirs for energy storage cannot be built. It does however have constant winds. Basic windmill technology was probably brought to Holland by the Spaniards, who had inherited the Netherlands and knew the Moorish windmill technology (Fig. 3). In place of slopes, there was wind in abundance, and so the first windmill “Molendinum venti” was built.

Because the population was growing, land was needed, but this could only be obtained through drainage. For this, pumps were necessary. The energy came from the windmills that drove the pumps and drained the land behind the dikes, thereby keeping it dry. From about 1600 onwards, windmills were also used to saw timber for the shipping industry. This allowed the Dutch to build ships in four months, whereas the English needed a year. The result was that Holland received a flood of shipbuilding orders from third countries. Even the Russian tsar Peter the Great took a closer look at Holland as a high-tech location. Albert Lortzing immortalised this in the opera “Zar und Zimmermann” [Tsar and Carpenter].

Fig. 3: Windmills were the number one source of energy in Holland, and also allowed the Dutch to build ships much faster than anyone else. But wood was also a construction material for use in windmills. Pine trunks from Bamberg's Hauptsmoorwald forest were particularly sought after for the long paddles of the windmills. Photo: PantherMedia / swisshippo (YAYMicro)

Organisation of purchasing

Holland was thus completely dependent on wood as a raw material. In this country with no raw materials of its own, trade alone was the foundation and motor of the economy. For successful trading, however, ships had to be built, so that the trading posts worldwide could be reached. The merchant fleet and the number of warships accompanying it increased steadily. New ships, and also repairs, consumed large quantities of wood. There was and is hardly any forest in Holland. But in the remote low mountain ranges of Germany there was still wood in abundance. Holland could access them via the Rhine. And so timber was rafted into the Netherlands from all corners of the Rhine catchment area. A particularly large number of rafts came from the Black Forest (via the Murg, Enns and Neckar rivers), the Frankenwald forest (via the Rodach and Main rivers) and from the Swiss mountains (via the Aare and Rhine).

The rafting era

Until the invention of the railway in the 19th century, water transport was the only means of transporting bulky timber over long distances. The Dutch also bought a lot of wood in the Baltic region and imported it by ship. Oak and semi-finished wooden products (boards, beams) were thus shipped from East Prussia to Holland from the 16th century onwards. Even today, the Baltic region plays an important role in the supply of timber to Great Britain and the Netherlands.

The raft - a hive of activity

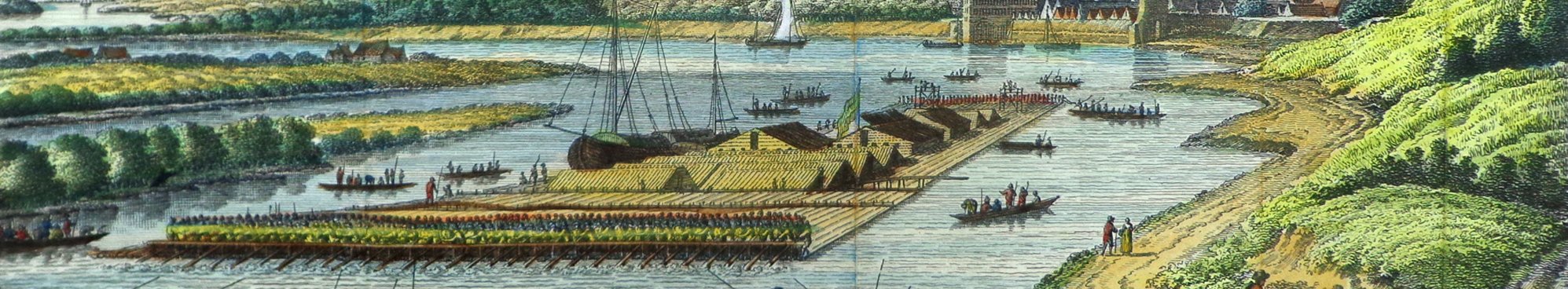

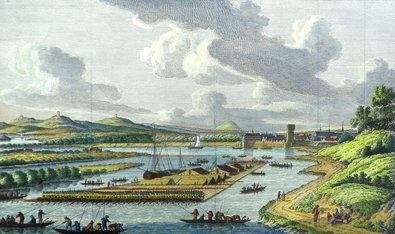

So Holland was the sales market for timber in Europe. In the Frankenwald forest, tributaries were straightened to make them passable for rafts of long timber. Timber trading companies such as the “Murgschifferschaft” trading company, the “Pforzheim raftsmen's guild”, or the “Calwer timber trade company” in the Black Forest were founded. Agents organised the purchase of timber. The timber was referred to as “Holländerholz”. The trade in Holländerholz roundwood was organised on a trans-regional basis. Rafts were re-tied several times on their way to the Netherlands (Fig. 4). On the River Rhine, the softwood rafts were up to 200 m long, and used to transport boards, poles, beams and other goods. They were also used for passenger transport, and rough huts were often built on them (Figures 5 and 6).

In 1520, Albrecht Dürer travelled on a raft along the Main and Rhine from Bamberg to the Netherlands, reporting numerous customs posts. Also notable was the pan-European trade in yew in the 16th and 17th centuries, which was organised from Nuremberg, and used the rafts for long-distance transport. Yew timber was used for bows and crossbows and its supply was thus a sensitive issue. It was cut in the Alps and transported on rafts via the Rhine to Holland, and from there by ship to England.

Crooked oak - especially valued

The rafts provided valuable space for transporting cargo, and often carried almost as much oak timber as the spruce and fir base could support. With increasing demand from Holland, the sorting of the timber was refined and standardised.

Unlike the firs and spruces destined for Holland, which were harvested in extensive harvesting operations over large areas, the oaks were selected and marketed individually. The length and diameter at the thinner end of “Holländer oaks” was precisely defined: they were to be 10-13 m long and have a diameter in the middle of 70-110 cm. Oak was in particularly high demand for shipbuilding, and was transported on the rafts as an additional cargo. This was the main reason for the dramatic decline in oak and maple in the Black Forest after the Thirty Years' War. The timber merchants wanted particular qualities of oak, and looked for particular shapes in the oak crowns (special assortments). Unlike today, in those days they were not interested in shafts that were as long and straight as possible; they were also looking for twigs, knots and steep branches that could be used for certain parts of the ships, which were preferably to be made from a single piece of timber. However, the huge foreign trade in oak also represented competition for domestic oak use (construction timber, barrel wood, pannage, etc.).

Ultimately, this is also the origin of the Heilbronn trunk wood grading system, a process in which - as with the Holländerholz timber - the timber is graded according to minimum length and minimum diameter at the thinner end. Rafting was used as a means of transport in Bavaria until the end of the 20th century.

For prince and people

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, a good half-dozen companies bought oak wood in the Spessart forest for trade with Holland. The export brought many florins into the coffers of the princely forest owners in the Spessart at that time. But the trade also benefited woodcutters and wagoners in the desperately poor Spessart villages. In the Krausenbach district in the Royal Bavarian Forestry Office of Bischbrunn, it was recorded that numerous Holländer logs were felled in 1830/1831 in the Waldameisensohl forest area and processed on site, so that the entire forest floor was covered with “chips” from the processed oaks. These chips had to be removed at a cost of 7 florins and 24 kreuzers because they were harmful to the young beech and oak trees.

Summary

From the 16th to the 19th centuries, numerous rafts - including some from Franconia and the Black Forest - went to Holland. A lot of wood was needed there to build harbour facilities, and a huge merchant fleet also developed to supply markets all over the world. Because the Netherlands had no forests of its own, its economic prosperity was based on the trade in strong coniferous logs, as well as oaks and special assortments.