Brief overview

- If the hornbeam is sufficiently vital, the risk of infection and damage from these fungi remains low

- Both pathogens currently occur in Baden-Württemberg only locally and not epidemically

- Stands that are experiencing increased stress from heat and drought as a result of climate change are expected to have an increased risk of infestation

- Sanitary logging to reduce the risk of infestation in the stand do not appear to be appropriate from a phytosanitary point of view

- Tree-related safety measures may be necessary as soon as there are indications of a risk of tree parts breaking off or the tree falling

The hornbeam can become diseased due to stress!

Due to its tolerance of heat, drought and frost, hornbeam is often used as a tree species on forest edges, as a secondary tree species in forest stands, and as an undemanding species in urban areas (Türk, 1996). In the context of climate change, it is being discussed as an alternative tree species in locations with a poor water supply and high temperatures. Due to its broad ecological amplitude, it can contribute to the diversity and stability of the forest. It is not particularly susceptible to damage caused by storms, drought and insect infestation. Infestation by insects occurs only to a limited extent (Redaktion FVA, 2021). Nevertheless, there have recently been increasing reports of damage to hornbeam related to fungal diseases.

Following a succession of above-averagely dry and warm years that began by 2018 at the latest, an increase in the death of hornbeams with a trunk diameter of 20 cm or more has recently been observed. In most cases, these are exposed trees on forest edges or in settlement areas (Cech 2019; Muser & Burgdorf, 2022). However, individual infections with fungi have also been recorded within forest stands. A combination between drought and heat stress with the associated weakening of the tree and the occurrence of new types of fungal damage in the bark seems likely.

The abiotic stress caused by heat and drought weakens hornbeams. The damage is exacerbated by saprophagous fungi, which colonise dead plant tissue. In particular two weakness dependent parasites, which often occur together on diseased trees, Anthostoma decipiens (hornbeam decline) and Cryphonectria carpinicola (bark canker of hornbeam), are presented below.

The pathogens

Teleomorph: Anthostoma decipiens

Anamorph: Cytospora decipiens

The pathogen Anthostoma decipiens has been known for over 100 years as a decomposer of deadwood, and first appeared as a pathogen is associated with hornbeam decline in northern Italy in the mid-1980s (Cech, 2019; Muser & Burgdorf, 2022). The bark pathogen has now also been detected throughout German-speaking countries, with some local hotspots (Express-PRA, 2019). The disease is also described in the literature using the terms “hornbeam dieback”, “hornbeam bark necrosis” or “Cryptospora canker”. In infection trials on deciduous tree species that are taxonomically or ecologically related to hornbeam (silver birch, sweet chestnut, hazelnut, copper beech, European hop-hornbeam, black alder, English oak), it was found that A. decipiens can cause bark lesions on these tested tree species (Saracchi et al., 2015). This allows us to conclude that this fungus is a potentially dangerous pathogen that can also infect tree species that share the same ecosystem as the hornbeam.

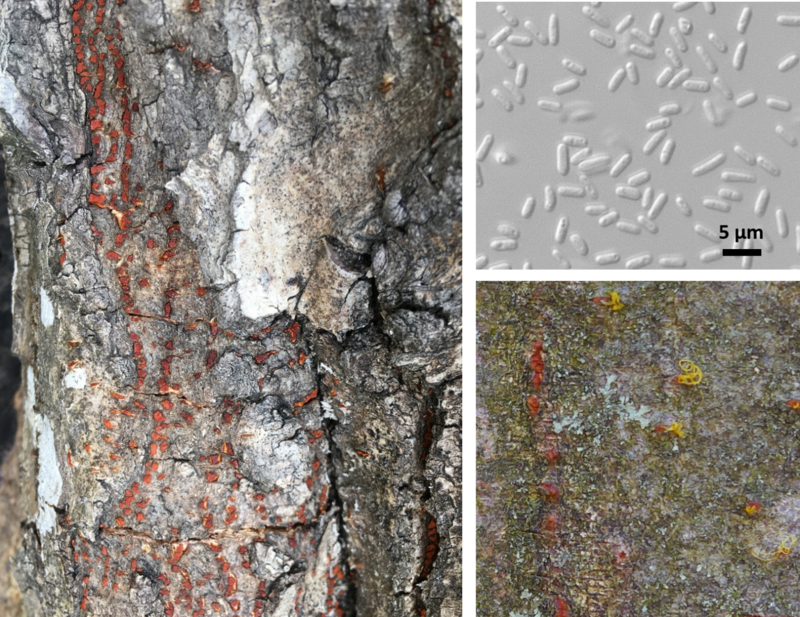

In its teleomorphic form, the fungus appears in the form of black hymenium on necrotic areas of bark. The German name “Geschnäbelter Kugelpilz” ("beaked ball fungus") is derived from this stage of development. The much more conspicuous anamorph form (Cytospora decipiens) is noticeable early on in bark lesions with red to reddish-orange coloured spore masses (Fig. 1). When fresh, they are lumpy and gelatinous to pasty; later they dry out and appear hard and glassy.

A. decipiens seems to occur primarily in specific locations, such as sunny, warm forest edges and exposed sites, along paths and in urban areas. The factors initiating the damage are generally heat and drought stress during the growing season (Fig. 2). It can be assumed that anthropogenic influences such as construction work along paths, accompanied by root damage or drastic changes in the water supply, may also also influence susceptibility to the disease.

Hornbeam bark canker

Telemorph: Cryphonectria carpinicola

Anamorph: Endothiella carpinicola

The Cryphonectria species Cryphonectria carpinicola, newly described in 2021 and specialised on the tree genus Carpinus, is believed to originate from Japan, as its sexual stage form has only been detected there so far (Cornejo et al., 2021; EPPO Alert List, 2024). It is not clear when this fungus arrived in Germany, as the disease has only become apparent in recent years due to the increased susceptibility of hornbeam to disease as a result of abiotic stress factors. C. carpinicola has a more restricted range of hosts in comparison with Anthostoma decipiens, and is considered to be less aggressive. The pathogen causing chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica) and the Mediterranean species C. radicalis are related to C. carpinicola. They are pathogens of their respective host tree species chestnut, oak and hornbeam. On sites where A. decipiens and C. carpinicola occur on hornbeam, sooty bark disease (Cryptostroma corticale) often also occurs on maple. This disease is also promoted by damaging factors such as heat in combination with drought.

In Europe, the pathogen has so far only appeared on bark in its anamorphic form Endothiellacarpinicola (Fig. 3). The symptoms of the disease are similar to those caused by A. decipiens. The two pathogens can occur simultaneously on the same tree. The brightly coloured orange spore tendrils of E. carpinicola are formed by fruiting bodies embedded in the bark. These often appear in longitudinally meandering, ribbon-like groups. This fungus is considered to be less virulent than A. decipiens, so that it is likely to cause less bark necrosis.

Infection and progress oft the disease

The two fungi differ in their ability to cause disease. A reduced resilience of the trees is considered to be a decisive factor for the development of disease caused by these fungi.

Both pathogens can be categorised as opportunistic parasites that take advantage of both wounds and weakness. Initially, cracks and open injuries to the bark tissue serve as entry points for the fungi. The symptoms of disease are typically sparse foliage, dieback of twigs, branches and sections of crown, as well as bark lesions on the trunk and stronger branches, which usually run longitudinally and are spiral-shaped or cover extensive areas. Infested bark areas show a sharp transition to healthy tissue (Cech, 2019). An infestation can lead to the death of affected parts of the tree and even to the death of the tree itself. The speed of progression of the disease and progression of the damage also depend on the severity of the infestation, the susceptibility of the tree and the extent of infection by other pathogens (Fig. 4). Depending on the growth conditions for the fungi, the course of the disease is usually sluggish, tending to develop gradually over several years or, in combination with other factors such as recurring periods of drought, more rapidly.

In connection with the bark lesions, infested hornbeams also show signs of the breeding of the hornbeam bark beetle (Scolytus carpini) and the fruit-tree pinhole borer (Xyleborinus saxesenii) (also known as the lesser shothole borer). The question of whether these bark beetles, longhorn beetles (Leiopus sp.) or jewel beetles (Agrilus olivicolor) act as precursors for these fungi by creating entry points via their boreholes or act as spore-carrying vectors for successful infection remains open. In addition, a white rot has been documented for Anthostoma decipiens. This can penetrate from the bark in a wedge shape towards the core (Muser & Burgdorf, 2022), whereas Cryphonectria carpinicola as a classic bark pathogen remains in the tissue without spreading to the wood tissue itself.