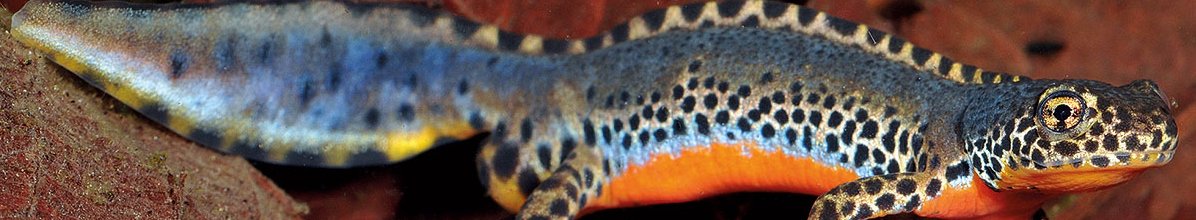

The alpine newt (Ichthyosaura alpestris) is our most attractive newt species, or at least it is in spring, when it dons its “aquatic livery” and takes on an almost tropical appearance. The Newt of the Year 2019 is our second biggest newt. It is distributed widely throughout central Europe and in many places it is a forest animal.

A blaze of tropical colour right on our doorstep

There are clear differences between the males and females. While the male animals grow to about 7-9 cm, the females reach a length of 7-12 cm. The alpine newt is thus bigger than our native palmate newt (Lissotriton helveticus) and common or European newt (Lissitriton vulgaris), but smaller than the crested newt (Triturus cristatus).

The sexes also differ in colour. The males have a particularly striking, unspotted, orangey-red belly, a very bluish upper side, and a silvery-white stripe with irregular dark spots along their flanks. Also striking is the smooth-edged crest with alternating black and yellowish white stripes that is clearly visible along their backs during the mating season. This dorsal crest is significantly reduced during the animals’ terrestrial phase, between June and March. The females have bluish-grey backs with a brownish, mottled pattern. Females also lack the dorsal crest.

Distribution

The range of the alpine newt stretches eastwards from north-western France, across northern Italy and southern Denmark and the Balkans to Romania and the Ukraine. In Germany this species is native to the south-western states. It does not occur in the north-east, and in the north-west it only occurs in patches. In Bavaria the alpine newt occurs mainly in densely forested areas such as the Spessart forest and Franconian Alb regions and in the foothills of the Alps. The elevation of their spawning grounds does not seem to be a major factor, ranging from 50 m a.s.l. in the north of Germany to over 2000 m a.s.l. in the Allgäu region. Along with the alpine salamander (Salamandra atra), the European common frog (Rana temporaria) and the common toad (Bufo bufo), the alpine newt is one of the few species to have made the alpine habitat its own.

Habitat

At lower and mid-range altitudes, the alpine newt is most often found in deciduous and mixed deciduous forests. The rich layer of litter in these forests is an important microhabitat that serves the newt both as a refuge and as a source of food. By contrast, it avoids pure spruce forests. At higher elevations in the Alps it is to be found above the tree line, often in bogs and in herbaceous areas and grassland.

It is extremely adaptable and not very selective in its choice of aquatic breeding grounds. It is satisfied as long as the land habitat around the water is adequate, and the water itself is not too contaminated and does not contain fish. Its preference is however for cooler, smaller bodies of water in or near forests. As well as in ponds, pools and gravel pits, the alpine newt is also to be found in road ditches, tyre tracks filled with water, and other temporary small bodies of water. It does not matter whether these are completely or partially in the shade, fully exposed to the sun, free of vegetation or full of weeds. A pond or puddle with a muddy bottom covered with leaves is sufficient.

During their terrestrial phase, the animals are largely nocturnal. They take refuge during the day in cool, moist hideouts close to their aquatic breeding grounds, hiding in fallen tree trunks and stumps, piles of deadwood, piles of stones, or the burrows of rodents. The alpine newt also uses these daytime hiding places for hibernation. Some of the alpine newt return to their spawning site in autumn to hibernate. It is extremely rare for alpine newt to move far from their spawning sites. They migrate between 100 m and 1000 m.

Breeding

The breeding season of the alpine newt is largely determined by the outside temperature. The newts are encouraged to migrate by persistent temperatures of over 5°C and high humidity levels. Most alpine newt begin moving towards their spawning sites in spring, usually from the middle of March, with the males going earlier than the females. This migration usually takes place up to two months later in the mountains, due to the lower temperatures.

A very elaborate courtship ritual begins in the water. The male alpine newt uses his tail to wave pheromones towards the female. At the end of the courtship dance, the male deposits a packet of sperm on the floor of the body of water, and the receptive female then picks it up with her cloaca. A few days after mating, the female lays between 70 and 400 eggs. In behaviour typical of all our native water newts, it wraps these individually in the leaves of water plants. The embryos take between 10 and 26 days to develop, and then the larvae hatch. The larvae develop over a further two to four months before metamorphosing into terrestrial juveniles with a length of 30-60 mm, migrating to suitable habitats from July to September.

Diet

Both the larvae and adult newts are considered to be generalists in terms of what they prey on. They take in different food, depending on availability in the respective body of water. Larvae feed primarily on small algae and move on to mainly water fleas (Cladocera) as they become bigger. In the water, adult alpine newts feed on freshwater flea shrimps (Gammarus fossarum), mosquito larvae, insects that have fallen into the water and earthworms, as well as the eggs and larvae of other amphibian species. Not infrequently, they also eat the eggs and larvae of their own species. On land the animals feed on insects and their larvae, as well as worms, woodlice and spiders.

Predators

The main predators taking adult alpine newts in the water include predatory fish as well as grass snakes. A co-existence of fish and newts in the same water is not possible in the long term, as most fish eat the spawn and young larvae of the alpine newt. Bodies of water that are avoided by fish because they are too shallow are thus advantageous for the alpine newt. Other predators include grey herons (Ardea cinerea), storks (Ciconiidae), white-throated dippers (Cinclus cinclus), great crested grebes (Podiceps cristatus), and ducks. On land, the main predators of the alpine newt are weasels (Mustela), martens (Mustelids), hedgehogs (Erinaceidae), shrews (Soricidae) and birds.

Threats

Because of its wide distribution, relatively large populations, preference for forests, lack of selectiveness when it comes to its aquatic breeding sites, and its adaptability, the alpine newt is still classified across Germany as “not threatened” on the “Red List” of endangered species. Nor is the alpine newt mentioned in the Habitats Directive. It does however have the status of a “strictly protected species” under the German federal law on nature protection (“Bundesnaturschutzgesetz”).

The alpine newt is nevertheless affected by habitat destruction and fragmentation. The improper use of harvesters and other machinery and the filling in of bodies of water can cause further problems for the species.

The biggest threat to alpine newt populations is fish stocking. This often applies when mountain lakes and ponds at higher altitudes are stocked with trout and char. Without extensive shallow water areas that are difficult or impossible for the fish to reach and that serve as refuge areas for the alpine newt, a co-existence of fish and newts is not possible in the long term.

Protective measures

Near existing populations, suitable bodies of water should be created, and efforts should be made to preserve existing ones, especially small and very small bodies of water. These are rapidly accepted by the alpine newt and can serve as stepping stones linking existing populations. Bodies of water like this should be kept free of fish. It is thus ideal if they sometimes dry out. When forest roads are built, water-channelling ditches should be preserved as far as possible, or created, maintained, and generally looked after in a way which minimises the impact on the newt.

The terrestrial habitat is also vital for the protection of the alpine newt. Cohesive forests are extremely important habitats for the alpine newt, offering not only spawning sites, but plenty of places to hide and hibernate during its terrestrial phase. The habitats of the alpine newt are significantly improved by increases in the amount of deadwood available, as well as the conversion of conifer-dominated forests to structurally rich deciduous and mixed deciduous forests. The use of machines in the immediate vicinity of bodies of water should also be reduced to a minimum.

Outside the forest, the alpine newt is dependent on connections between forest areas, consisting of extended hedgerows and wooded strips, high shrubland, and wet ditch systems between arable fields and pastures.