The detailed space-time behaviour of the chamois over the course of the year and day has not been investigated before in the Bavarian alpine region. As well as knowing the number of wild animals present in a particular region and their distribution across the area, it is important to know how they actually use the habitat, as habitat use is one of the key questions in animal ecology and wildlife management.

“Habitat” - the environment in which an animal species normally lives. The term comes from the Latin verb habitare, meaning “to inhabit” or “to live”. So where does the chamois actually “live”? This is not the easiest question to answer. Habitat use can vary considerably depending on the times of day and season, the age group, sex, or even individual animal. Findings on the habitat use and preferences of the chamois are not only interesting from an ecological point of view, but can also be an important basis for hoofed game management. They are important when it comes to issues such as the influence of human land use on the “living space” of the chamois, the visibility of the animals as part of the experience of recreational users of the forest, or hunting strategies.

As chamois in particular are often the subject of public discussion, the LWF project on “Integrative hoofed game management in the mountain forest” was expanded in 2018 to include the “Space-time behaviour and habitat use of the chamois”. The area between Vorderriss and Soiernspitze in the Karwendel region was selected as a study area. This area was already being studied intensively as part of the main project.

Determining and understanding differences in habitat use

Do chamois follow vegetation greening? When do they move after snowfall? How loyal are they to a particular area? The focus of the research is on answering questions like these on seasonal preferences and the influence of temporally varying factors such as the weather, vegetation, hunting or tourism. The chamois is affected both directly and indirectly in many ways by the increasing presence of humans in mountain regions, for example. Not all tourism, sports or hunting activities necessarily disturb the animals, but it is not unusual for their space-time behaviour to change as a reaction to human activities. Gender-specific differences in movements and habitat use will also be examined in greater detail in the evaluations.

How we capture chamois

To protect the animals, the safest and most effective method is always used to capture them. Two methods can basically be considered when it comes to fitting the chamois with transmitters: one is to use traps to capture them, and the second is to use an anaesthetic dart to immobilise them from a distance. The latter is however only possible in selected areas, as it is usually very difficult to get close enough to the animals. The animals also have to be in a safe area, so that they do not injure themselves in the time between being hit by the anaesthetic dart and the drug taking effect.

In our project the chamois are primarily captured using net traps (Fig. 2). With this type of trap, a net is initially laid out flat on the ground. At the touch of a button, counterweights are released, throwing the net suddenly upwards. Salt licks are used to attract the animal into the ring of netting, which has a diameter of approx. 15 m. Once an animal has activated the trap, it is freed from the net by the personnel present, and fitted with the transmitter collar. There is no need to use an anaesthetic for this method. After just a few minutes, the animal is released back into the wild with its transmitter fitted.

Detailed insights into the movements of the animals

To answer questions on seasonal habitat use, we generally require data that reflects the spatial use at any given time of the year with a high resolution. This is even more critical for the analysis of even more detailed processes, such as the concrete behaviour of the individual animal taking various factors of influence into account. Satellite telemetry is currently the method of choice for studies like this in wildlife research. This technology makes it possible to collect detailed geographical positioning data even for secretive species. Data like this gives us insights into “the world” of the tagged animal, which can then help us to understand processes such as perception and memory. High-resolution data thus provides an interface between the behavioural processes of individual animals, the ecology of populations, and management measures.

The activity sensor integrated in the GPS collars monitors and records the movement of the animal continuously by means of impulse counting (pedometer). As the sensor can also distinguish between a raised and lowered head, it is for example also possible to investigate whether an animal is particularly alert or not.

First chamois fitted with transmitters

Attempts to capture the first chamois began in the winter of 2018/19. In 2019, a total of five chamois - two bucks and three does - were fitted with transmitter collars (Fig. 3). A further 12 animals (six bucks and six does) followed in 2020. The gender ratio of the sample to date is thus roughly balanced. Every two hours, the collars transmit the exact coordinates of the tagged chamois. Over the course of a year, more than 4.000 relocations were thus recorded for each individual animal. The animals wear the transmitter collars for approximately a year, until they detach themselves automatically after the planned period with the help of a so-called “drop-off”. This ensures the GPS transmitter collars are shed gently, causing minimum stress to the animal.

Variability in seasonal habitat use

The initial results indicate that the seasonal spatial use varies considerably from animal to animal. The size of the foraging areas at different times of year also varies sometimes considerably from animal to animal.

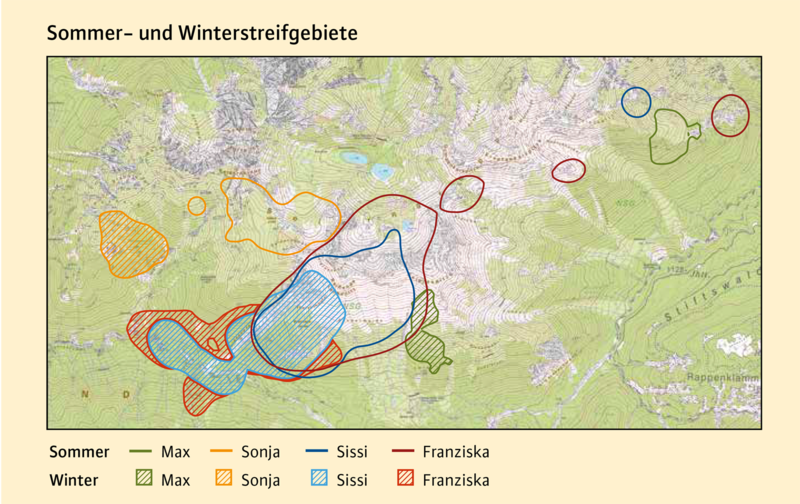

By way of example, Fig. 4 shows the summer and winter foraging areas of a chamois buck and three chamois does caught in 2019. Based on a kernel density estimation, an average range size of 133 ha was calculated for the summer quarter (June to August 2019), although one chamois in fact remained within an area of just 24 ha, while another individual animal roamed across an area of 313 ha during the same period. There was a tendency towards such differences during the winter quarter, too (January to March 2020), with the sizes of the foraging areas of the four animals ranging from 26 ha to 185 ha (115 ha on average).

As to be expected, the four tagged chamois in the Karwendel region used higher areas in summer (mean = 1.802 m above sea level) than in winter (mean = 1.597 m a.s.l.). On average, the tagged chamois were to be found on slightly steeper slopes in winter (mean = 39.31°) than in summer (mean = 34.14°). They also tended in both seasons to use south-facing slopes more.

The seasonal foraging areas of these four animals were an average of 2 km apart as the crow flies. Some individual animals showed classic seasonal shifts in their foraging areas, with clear separation between their summer and winter foraging areas, whereas other animals had a high degree of overlap between their seasonal foraging grounds. The chamois buck “Max” thus adhered faithfully to one particular site in summer, and migrated 3 km as the crow flies (taking the nature of the terrain into account, the distance is in fact far greater) to a separate foraging area in winter (Fig. 4). By contrast, the ranges frequented by the does “Sissi” and “Franziska” were far less differentiated according to season. They undertook shorter excursions in summer. The chamois doe “Sonja”, on the other hand, had small, clearly separated seasonal foraging areas.

The variation in the sizes of the seasonal foraging areas can be relatively well explained by the availability of resources and the individual territoriality of each animal or its needs with regard to the rearing of its young. Thanks to the variability in their movement patterns and spatial use, chamois can adapt well to seasonal changes in their habitat.

What is a “good” area for the chamois?

A first simple analysis of the composition of the habitats of the tagged chamois is carried out here just for the summer as an example. Using the data from the 17 chamois fitted to date with GPS transmitters, the preference or selection of the following landscape types was calculated for the months of June to August (2019 and 2020):

- Rocky regions with little vegetation

- Fields of Swiss mountain pine (Pinus mugo)

- Alpine grasslands and alpine pastures

- Forest (both mixed mountain forest and mainly coniferous forests)

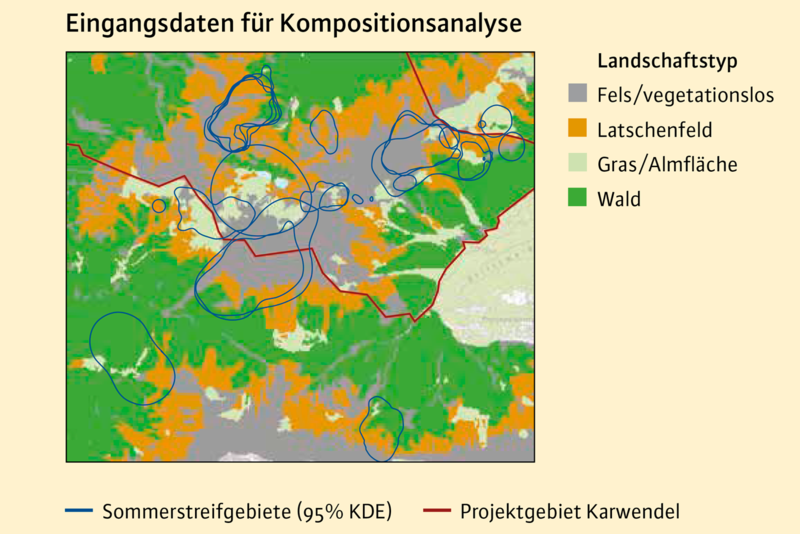

Whether particular landscape types are preferred by the tagged chamois also depends of course on how often these landscape types are to be found in the habitats. With the help of multi-variate analyses, the relative frequencies of use of a type of landscape within the foraging area of an animal can be compared with the potential availability of this type of landscape (Figs. 5 and 6).

Fig. 5: Input data for the multi-variate composition analysis. The proportion of the four landscape types (rock, mountain pine, grasland, wood) within the summer foraging areas is compared with the proportion generally available in the study area. The foraging areas of some individual animals overlap to a certain extent.

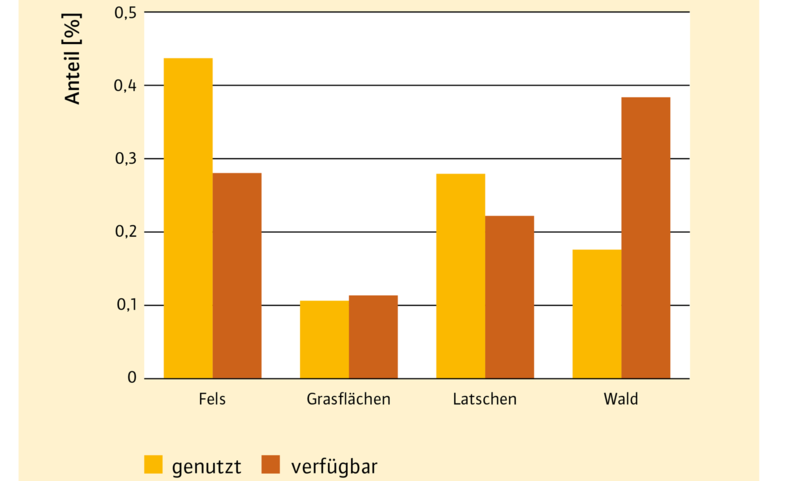

The results indicate that forest areas were visited less frequently than might have been expected based on the proportion of forest cover (Fig. 6), whereas fields of mountain pine and rocky regions were sought out more often. Grassy areas and alpine pastures were selected in line with their availability in the area, so that neither a preference nor an avoidance of these areas could be discerned in the Karwendel region. To summarise, it is clear that the summer foraging areas of the tagged chamois were mainly typical alpine habitat types, and that the tagged chamois in question preferred areas above the tree line.

Fig. 6: A comparison of the proportions of landscape types (rock, mountain pine, grasland, wood) actually used and potentially available in summer. The orange bars show the average rate of utilisation as an average for all the tagged chamois. The available proportions (brown) were the same for all animals in the area.

So what is next?

Due to the small sample size to date, the interpretation of the data must still be considered preliminary. Detailed evaluations of spatial use will follow in the course of the project, as soon as the data basis allows for statistically reliable statements. The daily activity phases of the chamois, their seasonal migration behaviour and the factors associated with these movements are of particular significance for the main project “Integral hoofed game management in mountain forests”.

Summary

The project “Telemetry of chamois in Bavaria” was initiated in 2018 in order to improve understanding of the spatial use behaviour of chamois. With the help of GPS collar transmitters, high resolution spatio-temporal movement data are being collected from individual chamois. The central objective of the research is to improve understanding of the complex interplay of ecological, climatic and human factors and their effects on the space-time behaviour of chamois. Preliminary findings indicate that the tagged chamois vary considerably in their seasonal use of space. The movement patterns observed to date show both classic seasonal migration with a clear separation between summer and winter foraging areas, and small-scale, year-round ranges with few seasonal shifts. Chamois are apparently able to adapt well to seasonal changes in their habitat thanks to the variability in their spatial use behaviour. More detailed evaluations of habitat use and the possible effects of human influences will follow once the necessary sample size has been reached in terms of the number of animals tagged and their distribution in the study area.

The project is being funded by the Bavarian State Ministry for Nutrition, Agriculture and Forests.