Are you familiar with Bavaria’s forest climate stations? Of course you are, because since 2006, every issue of LWFaktuell has included the weather and soil moisture report from the forest climate stations, including an assessment of the impact of the weather events of recent months on the forest in Bavaria. And again and again, you have also been able to read all sorts of articles both long and short - in LWFaktuell and in the forest condition reports - on the effects of sulphur, nitrogen or acid inputs into the forests, or on the growth and vitality reactions of trees – reports based on measurements from the forest climate stations. To mark the 35th anniversary of the forest climate stations, we would like to provide an insight into the inner workings of this intensive programme of forest environmental monitoring in Bavaria. But first, let's take a look at how it all began.

Boom in forest ecosystem research

The heated social debate about forest dieback in the 1980s was accompanied by an enormous boom in forest ecosystem research and intensive debate on environmental policy. Environmental influences were identified as being largely responsible for the widespread yellowing and thinning of the tree crowns, described at the time as “new forms of forest damage”. Pollutant influx and so-called “acid rain” were suspected to be the main culprits. Against this background, the annual forest condition survey was introduced in 1983, followed by the first soil condition survey in 1987. Both are carried out on a systematic grid covering the whole of Bavaria. The intensive measurement network of the forest climate stations was set up on the basis of resolutions passed by the Bavarian State Parliament in 1984, 1986 and 1991 to supplement two existing monitoring networks - the “Forest Condition Survey” and the “Soil Condition Survey” – and to allow the effects of environmental influences on the forest to be studied and monitored effectively. This decision was prompted by the experience gained from research into forest damage and forest ecosystems in the 1980s and unresolved questions regarding the effects of acid rain.

Fig. 2: Open-land measuring station of the FCS in Freising, with meteorological measuring instruments and precipitation collectors. Photo: Tobias Hase

A Bavaria-wide measuring network is created

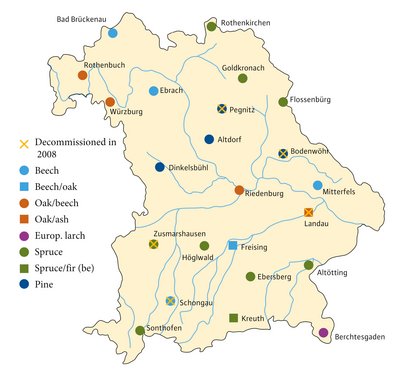

The installation of the first measuring facilities on two sites began in 1989. The first water samples to be analysed in the laboratory came from the forest climate station in Mitterfels. These were seepage water samples taken on 9 October 1990.

Soil water samples followed in the same year from the climate stations in Ebersberg (17.10.90), Riedenburg (24.10.90) and Altdorf (14.11.90). In November 1990, deposition measurement - the measurement of substance influxes via rain, fog and dust - also began at these four stations. Meteorological measurements on open areas also started in the same year. By 1997, the monitoring network had been expanded to comprise 22 stations. The last forest climate station to be opened was the measuring station in the former forestry office area of Kreuth in the Upper Bavarian Flysch Alps.

In a press release from 1990, Simon Nüssel, Bavarian Minister of Agriculture at the time, wrote: “With the forest climate measurement network, foresters and scientists will have a monitoring system that provides the essential data required for assessing the growth and vitality of forests. It will also be possible to identify climate changes in the forest at an early stage, to determine the current pollutant load of precipitation, soil moisture and the quality of water seepage into the groundwater, and to introduce appropriate measures to protect the forests”. This meant “a crucial prerequisite for the preservation of the forest ecosystem” had been created. Even then, Nüssel recognised the great potential of forest climate stations, which have now proven themselves as a reliable instrument for environmental monitoring in forests for 35 years.

In the 1990s, the focus of the monitoring was still on the effects of airborne pollutants in connection with what is now referred to as “Forest Dieback 1.0”. Thanks to the air pollution control measures taken at the time, air pollution with SO2 and thus “acid rain” have now been reduced substantially (Figure 3).

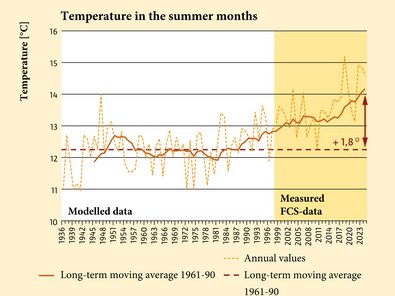

With the beginning of the new millennium, the consequences of global warming and climate change became increasingly noticeable – and also detectable at the forest climate stations (Figure 4). The associated effects on the forest are increasing and there is now talk of a new “Forest Dieback 2.0”. As Minister of Agriculture Nüssel predicted as early as 1990, the forest climate stations continue to provide important data required for fact-based political and silvicultural decisions to this day.

However, the Bavarian forest climate station programme does not stand alone. Instead, it is integrated into a comprehensive system of forest monitoring in Bavaria. There are particularly close links to the permanent soil monitoring areas in the forest and to the programmes for assessing the condition of tree crowns and soil. But also in a national context, the forest climate stations are Bavaria’s contribution to the German national network of intensive forest environmental monitoring within the framework of the Ordinance on Forest Environmental Monitoring (ForUmV). In addition, the Bavarian forest climate stations are part of the international Level 2 monitoring network of ICP Forests, based on the Geneva Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (UN-ECE CLRTAP).

The installation and operation of the stations were co-financed by the European Union until 2007. Today, the forest climate stations are financed exclusively by the Bavarian Forestry Administration.

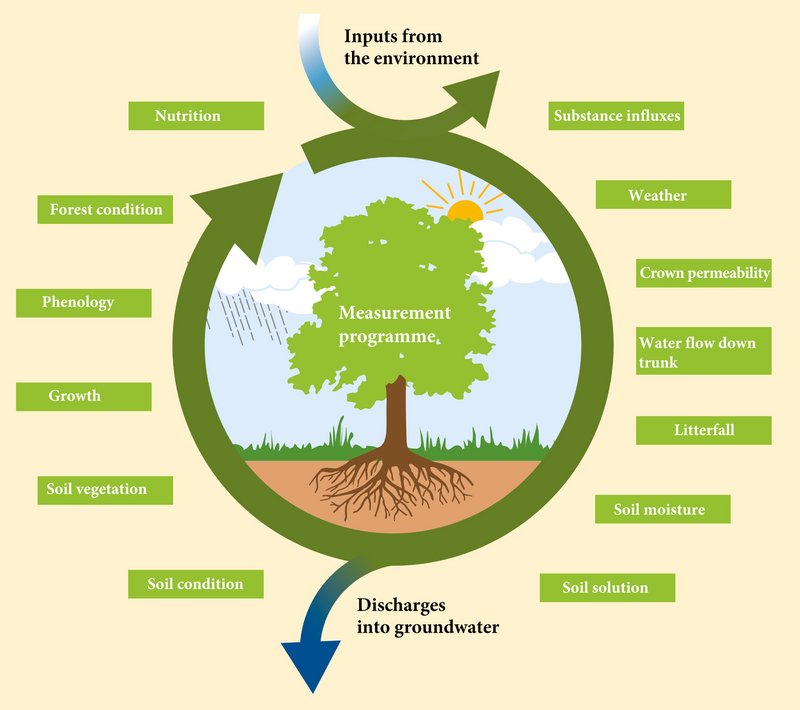

Key centres for national and international research

From the outset, the Forest Climate Stations programme aimed to record and document the complex chemical, physical and biological processes in the forest ecosystem - both under current environmental conditions and under those to be expected in the future. This has not changed to this day: In addition to the material balance (inputs, material movement in the soil down to the groundwater), the meteorological influencing factors and the water balance (evaporation, soil water storage, seepage water supply) of the forest are also analysed. At the same time and on the same site, the reactions of the forest trees to external influences are recorded, e.g. by means of growth measurements, vitality responses, determination of nutritional status, or seasonal development (Figure 5).

It is important that the programme is designed to be long-term, because only long-term measurements can identify stress-related changes in complex structures such as the forest ecosystem.

The forest climate stations are key centres of forestry research - today we could refer to them as “real-life laboratories”. They are also home to some of the nationwide network of permanent soil observation areas (“BDF”) and International Phenological Gardens (IPG). In addition, the FCS research stands are used by national and international researchers, who supplement their own project data with basic data collected at the stations. This promotes the pooling of forest ecology research in Bavaria’s forests and the exploitation of synergies - a key goal which has been implemented with great success for 35 years.

The motors behind the forest climate stations

Dr Andreas Knorr, Dr Martin Kennel, Georg Gietl, Dr Christian Kölling and Winfried Grimmeisen developed the concept for the forest climate stations at the instigation of Dr Robert Holzapfl, then President of the Munich Forest Research Institute (now LWF). In cooperation with the technician Günter Rosanitsch and the forestry engineer Heimo Neustifter, the installation of the first stations followed. As head of the “Soil and Climate” department at the LWF, Prof Dr Teja Preuhsler worked intensively to promote integration of the stations into the ICP Forests network. Under his leadership, the Bavarian network was also expanded to its current strength of 22 stations (Figure 6). Dr Martin Kennel managed the FCS from the beginning until 2003, before Hans-Peter Dietrich took over this role for almost 20 years until April 2022. The stations are looked after on site by staff from the local Offices for Food, Agriculture and Forestry (ÄELF). The supervisory officers and employees ensure smooth operation of the stations and are in direct contact with the programme coordinators at the LWF.

All samples from the forest climate stations are reliably analysed in our in-house laboratory. The exceptionally high quality standard is repeatedly confirmed by top results in ring tests carried out as part of the ICP Forest's international programme. The various programme sections of the stations are supervised scientifically by four departments of the LWF. Although not all those involved can be named here, we would like to take this opportunity to express our special thanks to everyone involved.

From sample to scientific evaluation

To illustrate the amount of work involved in the forest climate stations, let us take the example of a water sample. Below, we describe the route taken by a water sample from deposition collector or soil solution to scientific result.

As the sample is taken on-site, the water quantities are recorded on “sample sheets”, and parts of the sample are poured into laboratory bottles. These are stored in a refrigerator. Every four weeks, they are transported to the LWF. Once substance concentrations in each water sample have been recorded in the laboratory information system (LIMS), the data are merged with the water quantities in the FCS database and checked again in the time series and overall view. In order to subsequently calculate substance loads, the concentrations must be offset against the water volumes. For the deposition, the amount of water that has fallen is derived directly from the area-representative precipitation volumes in the deposition collectors. The water flows in the soil are calculated with the water balance model LWF-Brook90 using the meteorological measurement data from the open area. The substance flows are determined from the measured substance concentrations in the water and the modelled water flows. In the final step, substance balances for the analysed forest ecosystems are created from the individual substance flows.

Expansion and consolidation of the measurement programme for the future

As the site factors and expectations of the monitoring system have changed significantly over time, a concept for the future, “Forest Climate Stations 2050” (WKS2050), was developed in 2021 to meet the growing need for rapidly available and reliable information. Against the backdrop of current debate on tree species suitability and the success of forest conversion, the focus is primarily on questions relating to the water requirements of forests and water availability in the soil, as well as their effects on the growth and vitality of the forest. To answer these questions, the measurement programme at the existing sites is to be expanded, particularly with regard to recording soil moisture. For this purpose, further tree species comparisons are to be carried out at the same location. Particular attention will be paid to suitable climate-resilient tree species - in many cases, this means the conversion of spruce stands to beech/oak forest communities. At the same time, the increasingly frequent damage events and their effects are to be recorded promptly using new methods (e.g. sap flow measurements, remote sensing, drone flights, laser scanning).

Damage events, climatic changes and natural ageing processes do not stop at forest climate stations. In the forests around many FCS, the recent cluster of dry years (2015, 2018, 2019, 2022) has already led to massive impairment of vitality and bark beetle infestation. Together with the local forestry offices of the Bavarian State Forestry Company (BaySF) as on-site managers and our consultants at the State Forestry Administration offices ÄELF, we are therefore intensifying forest conversion efforts in favour of climate-resilient mixed forests and developing a silvicultural concept for all stations for the coming years. In addition, the measuring equipment, some of which has been in use for over 30 years, is now outdated and needs to be replaced. These measures will make the forest climate stations fit for the future.

Summary

For 35 years, environmental influences and their effects on the forest have been measured and evaluated at the Bavarian forest climate stations. This Bavaria-wide monitoring network, once focused primarily on recording air pollutants in the context of the “Waldsterben” or forest dieback debate, has also proven its worth in the current context of the issues related to the impact of climate change on our forests. While initially it was the decline in sulphur and acid pollution that could be documented, it is now primarily the consequences of climate change that are being monitored. If the comprehensive monitoring programme of the forest climate stations was not already in place, we would certainly have to set it up now - at the latest in light of recent forest damage and climate change. The programme has been running since 1990, giving us access to long and therefore extremely valuable series of measurements.