Sightings of the Asian longhorned beetle have been on the rise in Switzerland about 10 years ago. Along with the citrus longhorned beetle, another invasive pest, it poses a threat to various broadleaf tree species. Although both types of beetle have as yet only been spotted in residential areas, they may still spread to forests.

Fig. 1. Female Asian longhorned beetle (ALB). An exit hole can be seen at the bottom of the photograph. Photo: Beat Wermelinger (WSL)

Fig. 2. Female citrus longhorned beetle (CLB). Photo: Beat Wermelinger (WSL)

The introduction of dangerous animals and plants is not a new phenomenon in Europe. In Switzerland, the introduction of two types of longhorned beetle from Asia has been in the focus of public interest from about 2011 onwards. The Asian longhorned beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis, or ALB) is one of the most dangerous pests affecting broadleaf trees in the world. The citrus longhorned beetle (Anoplophora chinensis, or CLB) is distinctly less of a problem outside Asia. Both beetles are a threat to trees and bushes in residential areas and could also spread to nearby woodland areas or fruit crops. The potential damage of both harmful organisms as well as the costs for monitoring and combatting them are huge.

Appearance

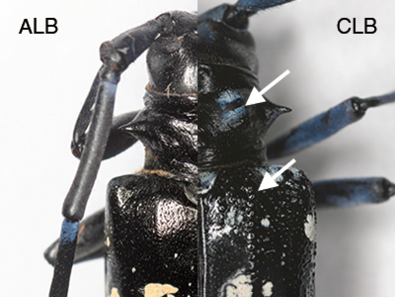

Both longhorned beetles are very large, with bodies measuring from 20 to 37 mm in length. They have long antennae, with the male’s antennae measuring more than double their body length and the female’s antennae being nearly twice as long as their body (see Fig. 1 and 2). The antennae of both males and females are covered in bands of black and light blue-grey. The beetle’s distinctive shiny black elytra are covered in irregular, usually white spots, and the pronotum bears two sharp lateral spikes.

The main difference between adult ALBs and CLBs is the appearance of the elytra bases. While the front fifth of the CLB’s elytra is clearly granulated, the ALB’s entire elytra appear smooth throughout, although they are finely punctured (Fig. 3). The Japanese form of the CLB (malasiaca form) also has two white-blue markings on its pronotum, which the ALB does not have.

Fig. 3. Difference between ALB and CLB: The citrus longhorned beetle’s elytra base is granulated, and the malasiaca form has blue-white markings on the pronotum. Photo: Beat Wermelinger (WSL)

Fig. 4. Citrus longhorned beetle larva with the typical pattern on its pronotal shield. Photo: Beat Wermelinger (WSL)

The apodous larvae of both beetles are approximately 5 cm long and have a crenelated pronotal shield (Fig. 4). CLB larvae have a second, poorly visible band. However, only a genetic analysis can reliably differentiate between the two species, especially between young CLB and ALB larvae.

Life cycle

Both longhorned beetles have very similar development cycles. The cycle for the Asian longhorned beetle will be used here to represent that of both species (see Fig. 5).

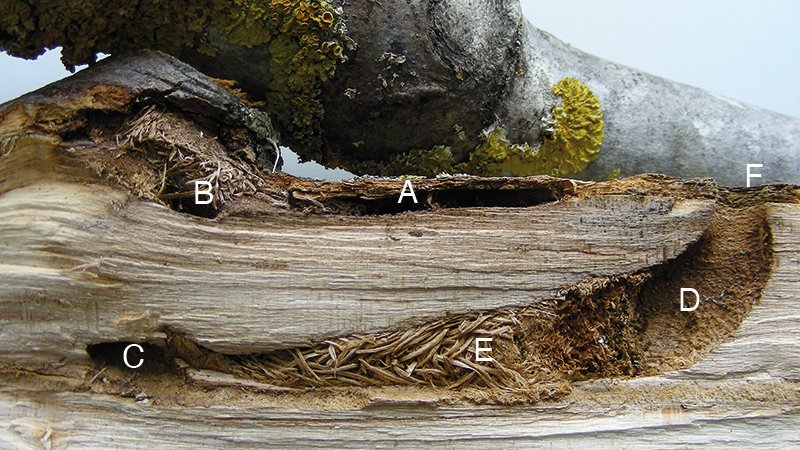

Fig. 5. Feeding gallery of an Asian longhorned beetle in a maple tree. The young larva first feeds in the phloem under the bark (A), then works its way into the wood (B) and creates a wide larval tunnel (C). The end of the tunnel opens up into a pupation chamber (D) plugged with shavings (E), where the larva molts into a pupa. Finally, the adult beetle exits the tree via a round hole (F). Photo: Doris Hölling (WSL)

The female gnaws a funnel-shaped pit or a slit in the bark of the trunk or branches of the host tree and lays one egg between the phloem and sapwood in each one. A female usually deposits between 30 and 60 eggs in total, although they can lay up to 200. After one to two weeks, the larva hatches and begins to feed on the phloem. Early-stage larvae need bark from living trees. After the third larval stage, the larva works its way into the wood and hollows out an oval tunnel (10 to 30 cm long), moving up the trunk. The resulting frass (fine at first, then becoming coarser) can be observed on the trunk, the foot of the tree or branch forks.

The larva pupates at the end of the tunnel. After a pupal stage lasting two to three weeks (Fig. 6), the adult beetle remains in the pupation chamber for one to two weeks after its metamorphosis and then gnaws a round hole of approximately 1 cm in diameter (Fig. 1), usually on the branch or trunk above the site where the egg was laid.

Fig. 6. Pupa of the Asian longhorned beetle. Photo: Doris Hölling (WSL)

Fig. 7. Maturation feeding of an Asian longhorned beetle on the bark of young shoots. Photo: Markus Hochstrasser

Once they have emerged, the beetles undergo a period of maturation feeding in the treetop, eating still unlignified bark of young shoots or sometimes leaves and leaf petioles (Fig. 7). If the tree is still sufficiently healthy, the beetles often remain in the tree where they emerged to lay their own eggs. The beetles are quite slow and only fly on hot, sunny days. However, most of them do not venture far from their host tree if there are suitable breeding trees nearby. The beetle’s flight period lasts the entire vegetation period from April to October, being concentrated between June and August. In Central Europe, a generation usually takes two years to develop.

In contrast to the biology of the Asian longhorned beetle, female citrus longhorned beetles create T-shaped slits or small funnel-shaped pits to lay their eggs, usually at the base of the tree or in the surface roots. During the larval development stage, distinctive frass caused by tunnelling can usually be observed at the roots. Around 90% of beetles develop in the underground roots. Exit holes created by CLB (average diameter of 10 to 15 mm) are somewhat larger than those of ALBs and are located at the base of the tree and the roots (Fig.8). The beetles predominantly fly between May and July.

Fig. 8. Exit holes of numerous citrus longhorned beetles. Photo: Matteo Maspero

Fig. 9. Wood packaging containing stone imported from East Asia is the most common way for ALBs to enter a country. Photo: Beat Forster (WSL)

Host plants and economic damage

Fig. 10. CLB are introduced via ornamental plants, such as this Japanese maple. A larva developed underground at the foot of this tree. Photo: Beat Wermelinger (WSL)

Both species of beetle infest solely living broadleaf trees and shrubs of all types and ages that are at least 3 cm in diameter, with the most common hosts in Europe being maples, birches, willows, horse chestnuts and poplars. In China, citrus longhorned beetles primarily damage citrus fruit trees, hence the name.

In contrast to most native longhorned beetles, both Asian species attack healthy plants. Larvae devour tissue and damage the vessels of the bark phloem and sapwood and thus disrupt the sap flow. A complete disruption causes the tree to die. Feeding in the bark causes sap to leak and opens the door to fungal infestations. Even a small infestation will kill young host trees with small trunks. Older trees better withstand a limited level of feeding of individual larvae. However, heavier and continuing infestations over several generations also weaken full-grown trees to the point of being lethal.

ALBs are now one of the world’s most dangerous pests for broadleaf trees and shrubs. The climate conditions in Europe are conducive to infestations and the risk of these insects being introduced is high as a result of extensive trade with China (wood packaging material and ornamental plants, Fig. 9 and 10). Virtually all infestations in the USA and Europe to date involve trees in towns and parks in residential or industrial areas. There is generally considerable potential for damage, as the beetles infest different types of healthy broadleaf trees and appear in various climate regions. There is no native longhorned beetle species that shows such potential for damage.

In the USA, tens of thousands of trees in residential areas have been felled and chipped to date. The cost of the damage already runs to over half a billion dollars. A study has estimated that if ALB spreads to all urban areas in the USA, up to 30% of trees will die, resulting in several hundred billion dollars’ worth of damage.

In Braunau, Austria, the site of the first ALB infestation in Europe, some €2 million was spent on combatting and monitoring this pest between 2001 and 2006. In the Milan region in Italy, CLBs infested an area spanning 400 km2. By 2011, around 25,000 trees had been cut down, 17,000 of which were infested. Monitoring and combatting CLB in this area has cost €18 million to date.

Are natural forests in danger?

Little is currently known about the damage potential of ALB in natural forests. In contrast to the situation in the USA, natural forest areas close to infestation sites in Europe and China have been largely spared from any spread of the infestation. However, a risk analysis for Europe demonstrated that it is possible that the beetles may infest forest trees.

It would be extremely expensive to monitor and combat the beetles if they were to spread to forests. If the beetles were to establish a foothold there, this would seriously restrict the wood trade both at home and abroad. In addition to the economic and social impact, there is also the issue of the ecological consequences of a wide-scale spread of these beetles. Based on current levels of knowledge, we can only speculate on what would happen. A regional-level cut in numbers of some of the main host tree species could be possible, but this would have hardly have serious impact on any organisms associated with these trees.

Measures

Fig. 11. Trees infested by either type of invasive longhorned beetle must be removed and chopped up or burned. All surrounding trees then need to be thoroughly checked for any infestation. Photo: Doris Hölling (WSL)

Fig. 12. A climber checks a trunk for signs of an ALB infestation. It will be extremely expensive to monitor and combat the beetles if they spread to the forests. Photo: Doris Hölling (WSL)

Preventing the introduction of quarantine organisms both by respecting import regulations and checking imported goods are the number one measures.

Once an infestation has been identified, successful eradication is contingent as soon as possible. As ALB is a slow flier and needs at most two years to fully develop within wood, it is realistic to hope that smaller infestations can be eradicated. All infested wood, as well as infested wooden products such as crates, pallets or firewood, must be immediately destroyed, either by being chopped up (Fig. 11) and/or burned. The stumps of trees infested with CLBs must also be destroyed.

As well as getting rid of infested wood, also neighbouring, potential host plants should be removed as a preventive measure. If this is not feasible, the remaining trees must be thoroughly checked several times a year (Fig. 12). Furthermore, no hardwood may leave the infestation area if it has not been treated and extensively checked beforehand. This applies to timber, firewood, tree-cutting material and nursery plants.

Please do not confuse with native beetles!

It is crucial that excessive caution does not result in all trees showing traces of insect feeding or holes being destroyed. Many native species of beetles and other wood insects, some of which are rare and endangered, depend upon old, weak or dying trees.

If there are no grounds to suspect an ALB or CLB infestation, trees must be left alone, particularly older, richly structured trees with holes, larval galleries, boring dust or wounds as an essential habitat for a multitude of insects, birds, fungi, plants and lichen (see www.totholz.ch, available in German or French).

Order

You can also order printed versions of Invasive Asian longhorned beetles (in german, french and italian) from WSL:

WSL e-shop

Zürcherstrasse 111

CH-8903 Birmensdorf

e-shop@wsl.ch

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/assets/_processed_/6/0/csm_wsl_alb_europa_weiss_e3f367e50a.jpeg)